(continues..)

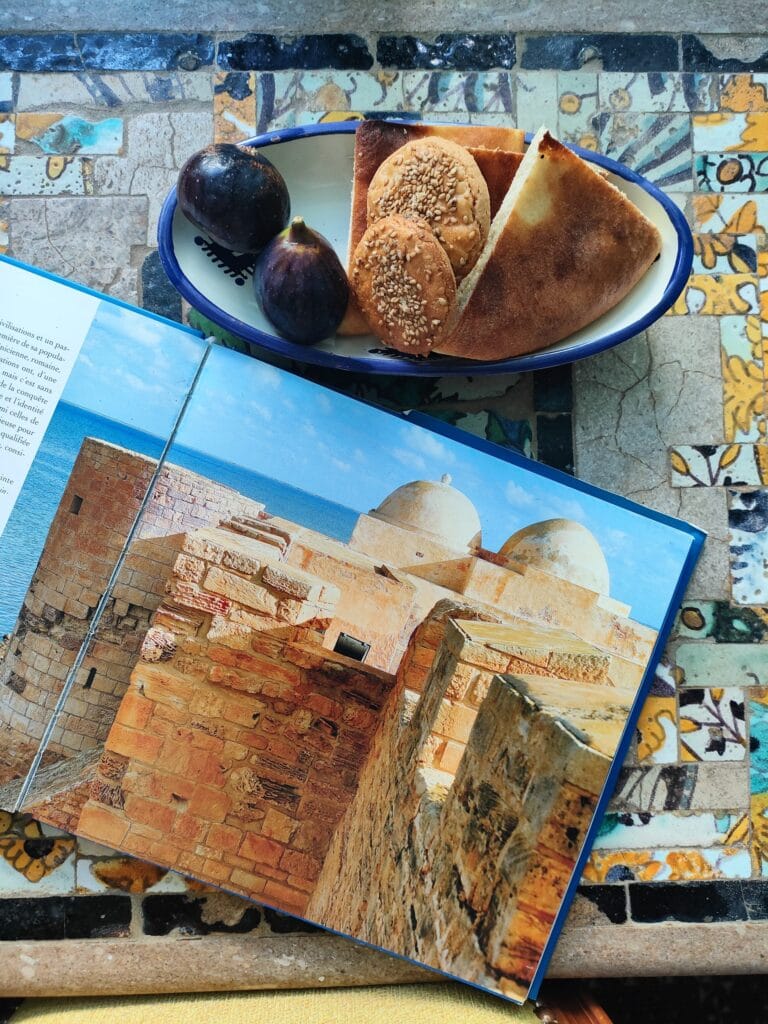

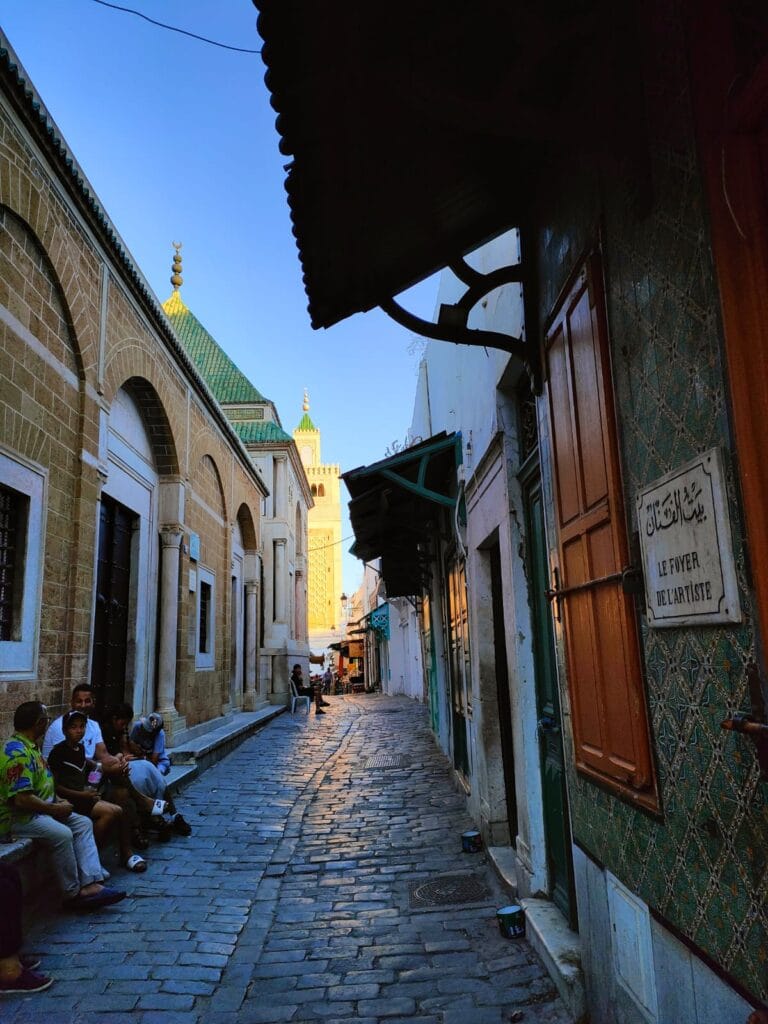

The Medina of Tunis is very ancient, dating back to the 7th century A.D., covering an area of 300 hectares and animated by one tenth of Tunis’ population. Being indeed very densely inhabited compared to others, it is home to a wide variety of hammams, madrasas, fondouks, dar, as well as the great Al-Zaytuna Mosque, the second largest mosque in Tunisia after the Kairouan complex, commissioned by a distant Umayyad ruler in the 8th century.

A well-known centre for the dissemination of Islamic culture, Al Zaytuna was once home to the University of Religious Studies, later dismissed by the secularist Habib Bourguiba in the mid-1950s and the later Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali in an attempt to compress any influence of the Islamist Ennahda party. The same party that, until the 2011 Jasmine Revolution, had been outlawed due to its affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood movement, keeping its leader Rachid Gannoushi relegated to exile in London. Back in his homeland, he led the party to victory in the 2011 constituent elections, registering 37% of the vote, speaking of an Arab Spring, of a democratic renaissance, of democratic Islamism. A flash in the pan, in reality, apart from the victory of the current first female mayor of Tunis Souad Abderrahim, who belongs to this party. Today’s loss of consensus after a decade of coalition government is inexorable. The rebirth that the revolution should have promised collides with the rampant economic crisis, corruption, inflation, foreign debt. As a political crisis breaks out, the President of the Republic Kais Saied dissolves Parliament in July 2021, writing a new Constitution that reduces the prerogatives of the Chambers and the independence of the judiciary. People approve it. But then, in the following parliamentary elections, electoral disaffection emerges, 9 % of the eligible voters go to the polls. A world record abstention. The Bardo Museum, which I so much wanted to visit, because of the richest display of Roman mosaics in the world, is closed to the public precisely because it is adjacent to the Parliament building, which is banned. Saied is perched in his palace/magnificent presidential mansion on the Carthaginian shores, then Rachid Gannouchi is arrested in April 2023 and later on he begins a hunger strike from prison. To share his detention there are several other journalists and opponents of the regime. After all, we are in the Maghreb, no one had believed in the possibility of an impromptu invention of democracy when distinguished analysts spoke of the virtuous ‘Tunisian model’ in 2011. At least, back then, I didn’t believe it.

Downtown – Avenue Bourguiba

Anyway, as we approach the downtown it’s time to be lured by a weirdo who does his best to get his tip while recommending the most local restaurant in Tunis, Chez Slah, before ending up at the Greek Orthodox Church of St George. The history of this community intrigues me – what are they doing here? In 1649, the first Greek slaves freed from Ottoman occupation were concentrated in Tunis, Sfax, Djerba. In the 19th century, even the former Grand Vizier Khaznadar was originally from a Greek island, Chios. Fully integrated into Tunisian society, they learnt French during the colonial period, maintaining the use of Greek in the orthodox liturgy, which in Tunisia is still frequently contaminated with the Russian Orthodox one, resulting the respective priests often officiating together. With 99% of the population Islamic, Tunisia today seems to continue to be the republican and open state established by Habib Bourguiba in 1956, a carrefour of civilisations and religions, unlike its more closed and conservative neighbours. Will it continue to be so? Well, the 2022 Constitution leaves scenarios open, in the ambiguity of Article 5 – La Tunisie constitue une partie de la nation islamique. Seul l’Etat doit œuvrer, dans un régime démocratique, à la réalisation des vocations de l’Islam authentique qui consistent à préserver la vie, l’honneur, les biens, la religion et la liberté.

Returning to Medina for dinner, by the way, we come across the cultural centre named after Taher al Haddad, the visionary intellectual who, misunderstood and therefore outcast, wrote Our Woman in Sharia and Society in 1930, the basis of what in 1957 became the new family code, again thanks to Bourguiba. The same code that revolutionised the legislative system and affirmed the principle of secularism and equality to guarantee the fundamental rights of the individual, freeing marriage and the position of women in the family and society from Muslim law. This blessed text abolished polygamy, created a procedure for divorce, and banned forced marriages. Haddad’s influence was so crucial that it called into question the legacy of colonial power, rediscussing the country’s cultural identity, so much that even today extremist groups and the Ennahda party still consider valid the ‘excommunication’ (takfīr) through which the Al Zaytuna Mosque declared al-Ḥaddād an enemy of the Islamic nation, the very institution where the intellectual was educated, about a century ago. In the same ratio, after quite a time, al-Ḥaddād’s statue has been recently attacked in his home village in the Gabes area.

To tell the story of Tunisia’s most revolutionary reformer of the 20th century is Amira Ghenim’s powerful literary production, The House of Notables. This novel deals with the story of eleven characters by interweaving the intergenerational micro-history of two families of Tunisian notables from the capital city with the events of public and national macro-history, from the beginning of the 20th century to the dawn of the Arab Spring. Inadvertently, Al Haddad, of humble origins, falls in love with the beautiful, cultured and upper-class Zubayda, enthralling her with the Arabic-Islamic language and culture through his lessons, which complement the French-colonial education of the high-society young woman. In these guises, not only does al Haddad emerge as a proud herald of Arabic-speaking culture, but in the course of the novel he also reveals himself as an active co-founder, together with Muhammad ‘Alī al-Ḥāmmī, of the first Tunisian trade union (1924). Through the voice of Zubayda, of the other characters, friends and foes alike, Al Haddad stands out as a decisive and clairvoyant historical figure in the context of an intellectual and ruling class that lacks political vision and is intent on defending its privileges and shrouding its reputation in the code of silence of the most stifling conveniences. Towards the end of the novel, the voice of Zubayda’s granddaughter, Hind, narrates how the events of the 1930s still affect contemporary figures. She recounts the dramatic events in Tunisia from the bloody bread riots of January 1984 to the revolution of 2011, denouncing the hypocrisy of the Tunisian left, which, by deliberately riding roughshod over the revolutions, has nevertheless continued to stagnate in a retrograde and macho mentality.

And so, in the margins of this book and in front of the cultural centre of al-Haddad, I ask myself..after sixty years, how do the laws and claims of secularism still coexist with the rich Muslim cultural substratum? Is it possible to imagine a valuable synthesis, or is it pure utopia?

After all, it is only time, as the sun sets, for a good glass of wine. A Magon from the vineyards of Carthage, named after a famous Punic agronomist. Intense, structured, excellent for meditation, especially on the roofs of Dar El Jeld, a charming old palace at the gates of the Medina, near the Kasbah. It is a brisk, breezy evening, like many of those spent in our Mediterranean. We gather around an elegant white table, tired, pampered by the sensual notes of chansons francaises, to the rhythm of saxophones. I ask for a pashmina to protect me from the sudden coolness that always presses summer nights near the sea, while I wait, on the flat white roofs of Tunis, for the African sun to come down and colour them orange, red, purple, blue…