An ordinary Wednesday. Flight at noon, destination Tel Aviv.

It was 9 a.m., the Israeli flight company Elal was asking to show up at the gate three hours in advance. In line with me were groups of pilgrims waiting to embark for the ‘Holy Land’, more or less young, then me. Departing for Israel is not that simple. Every passenger has to undergo questions from the cabin crew before checking in, sometimes also baggage inspections. The questions are of general, personal and logistical nature. Travelling in a group is easier than travelling alone, as the reason for the trip is quickly stated. Whereas, as for me, I did not believe that a young 22-year-old graduate could prove a suspect for the State of Israel, but already that morning I realised that the reason for a young student heading to Tel Aviv alone, or at least in the company of his mother, might not be so genuine. “Who packed your luggage?” “Were you the last person to close your suitcase?” “Who took you to the airport?” “What is your relationship with the person next to you?” “What reason brings you to Israel?” “Are you staying with someone once you are there?” “What city are you visiting?” “Why are you studying languages?” “Have you graduated?” “And what will you do afterwards?” Strange, I had been told that Tel Aviv was the city of freedom.

It was on the Elal flight that I tasted my first Israeli hummus, along with pita and kobe (meat and semolina balls). Time to try reading a few Israeli newspapers, listen to the hits from the other side of the Mediterranean and the conversations of my neighbours, who were whispering in that strange guttural language, and I was soon on the coast of Tel Aviv, the city built in the early 20th century on the sands of the ancient port of Jaffa.

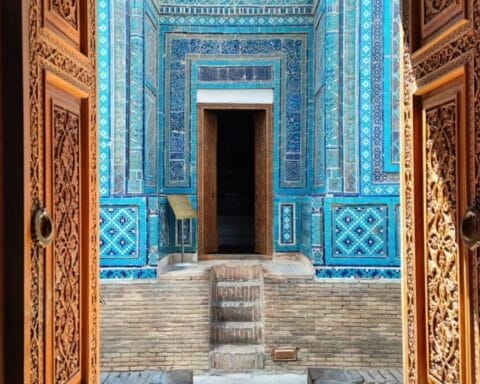

Landing at Ben Gurion is the equivalent of crossing paths with believers of all creeds from the five continents. Welcoming us are the billboards of the local star, Bar Refaeli, both at the airport and in every corner of the city. Her languid gaze rests on every soul in the capital. We step outside, the heat is slowly released by the asphalt, still laden with sunshine. We take a taxi to our flat behind Rotschild Avenue. Our taxi driver is an Uzbek Jew, we communicate in Russian, driving into the city at sunset, between palm trees and skyscrapers. Perhaps I was expecting a little Beverly Hills, but I soon find a chaotic Athens with shabby old buildings and cluttered common spaces. I realise I am very much in the south, and I like the idea. A judia (Jewish) from Argentina runs my aparthotel, and it is by communicating in Spanish that she leads me to my room.

I thought that only English could save me from Hebrew and Arabic, but I soon realised that English would be the last language of communication. I leave the house for dinner, two steps into the Rotschild and head for the sea. I reach the endless promenade of Tel Aviv’s skyscrapers, an open sea-front from Jaffa to the commercial port, miles of free beach and bike paths, filled with beach volleyball courts and lively clubs, especially at night, at the end of October, with 25 degrees dry air. There are those who run, those who sip a drink barefoot by the sea, those who start a beach game, those who do yoga, those who stroll, it feels like a midsummer night. On one side there are kilometre-long glass buildings, on the other the wild beach, where some businessmen in suits take off their jackets and shoes after work to go down to the sea. Then the Tel Aviv marina, a quadrangle of trendy places where we dine and bite into our first kebab, with a glass of arak (raki), an army of appetisers and an assortment of spreadable sauces on pita bread, from tahina to hummus to skhug (chilli and spice sauce). A hefty bill, but Tel Aviv is like that – trendy, fun and expensive – and tipping is a must.

It is late, and in Tel Aviv’s most avant-garde district we choose to take the city’s most popular means of transport, the sharut. The sharut is a shared Soviet-style minibus serving various districts of the city. Yellow and marked with different numbers according to the areas it covers, it stops at the hitchhiking signal at any street corner, and likewise releases passengers at the fixed price of 5.9 shekels, passed from hand to hand to the driver, even in front of the home address. In a metropolis where buses routinely end up stuck in traffic and the metro awaits completion in 2022, the sharut is still the life-saving means of transport for citizens, along with bikes. One day, it is rumored here, also self-driving cars will be an asset.

(continues..)