I am on the Boka Kotorska Bay, on top of a steep rise that allows me to dominate it while noticing its various inlets, the view is breathtaking. This stretch of water, sheltered and protected by a series of fjords running inland, was for centuries the impregnable naval-military base of the Serenissima of Venice, then of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. From here, the Venetians attacked the Adriatic corsairs and regrouped to launch lashing ambushes or counter-offensives against the Ottoman Turks stationed in Herzeg Novi. Sometimes they even allied themselves with the Sultan’s army to fight the common indigenous Montenegrin enemy, like the time when Scepan Mali, posing as Tsar Peter III, managed to defeat the Venetian-Ottoman axis in Kotor in 1770. The Venetians left shortly after that year, in 1797, with the Treaty of Campoformio, leaving behind language, culture and the magnificent architecture of the former overseas outposts on the Adriatic coast. Today, Montenegro boasts chic locations like Budva, Perasto, Tivat, architectural gems like Castelnovo, Kotor, Bar, Shkodra. However, even though I am a daughter of the Serenissima, I know the real reason that led me to visit this country.

It was because of Carlo Yriarte and his travelogue ‘Montenegro’, where he described the Montenegrins as an indomitable, warlike, proud people. I became curious. He visited the Balkans in the 19th century, travelling through the fault lines of Dalmatia and arriving in the de facto independent stronghold of the Montenegrins, in Cetinje, subject to frequent incursions by the Ottomans. There, the vladika, a temporal and spiritual leader who recognised neither the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople nor the Moscow Synod, had his seat at the Biljarda palace. Only with the vladika Danilo I, in 1852, did a dynasty of secular primogeniture begin, and in 1878, at the Congress of Berlin, Nicholas I Prince of Montenegro finally obtained de jure independence at the table of the European powers, certainly also thanks to the firm endorsement of the Russian Empire, drunk with pan-Slavic ambitions. The reason for my interest in Cetinje, a city forgotten by all tourist guides and fallen into oblivion since grey Podgorica became the new capital, starts right here.

To get there, as I was saying, I leave the view of the Boka Kotorska Bay early in the morning and start driving up the Montenegrin hinterland through the serpentine precipice, one of the most dangerous roads in Europe according to Google. In the country’s hinterland, only long stretches of green meadows, sparse wooden villages and farms where they produce the phantom pršut, Montenegrin culinary pride. As I approach one of them, I am intimidated by an angry swarm of dominant hens. A very different scenario from coastal Montenegro, refined, opulent, but I must say I like this change of register in just 40 km.

Then I land in Cetinje, in fact a large, quiet village where the residence of the President of Montenegro is still located. My rented skoda meanders through the orthogonal avenues of the town, spotting here and there widespread billboards indicating local Chinese-financed public works, they are even in double language. It is certainly not unknown that Montenegro is now a land of investment by Russian, Chinese, Turkish and European funds. Who will prevail? Who will be able to establish complete influence? Who knows, perhaps no one. For now, Montenegro joined NATO in 2017, with a clear stance, muscularly speaking. Moreover, it has been granted EU candidate status since 2010, only four years after seceding from the state of Serbia and Montenegro. What urgency! But for whom? For the Union? Or for Montenegro, gripped by the lust to stage this irresistible balancing act between great powers and the desire to disengage from a greedy neighbour? Only in Cetinje would I have understood any of this.

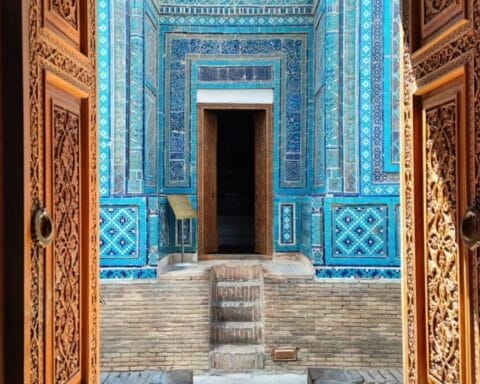

The identity history of today’s Montenegro was born here. No one speaks English, at most they speak a little Italian or Russian. I sit down for steaming cevapcici and a Niksicko beer at the Crna Gora inn. I can only read the menu thanks to a guy from Podgorica who also orders for me. They are the best I have tried in the country! I carry out a thorough quality control of these meatballs at every inn I choose to stop at. Trying to make my way towards the city centre later on, I come across long deep red murals extolling the eighty years (1941-2021) of the Ustanka (revolution), when Montenegrin communist partisans rebelled against the Cetnian forces and the fascist Italian occupation. The communists, backed by British support, would later characterise the post-war Montenegrin establishment into the form of Balkan, multinational, non-aligned real socialism that defined the new Yugoslavia. Such a project of the charismatic Marshal Josif Broz Tito, a catalyst of consensus, seemed to run smoothly. However, it only lasted reasonably until 1980, the year of his death, after which all plunged back into the morass of regionalism. Orphaned of the unifying force of the leader, in Montenegro refluxed that identity revanchism magnified right by the symbols found in Cetinje itself, home to the iconic Biljarda, foreign embassies and the royal palace of late 19th century foundation. In fact, Cetinje was the symbol of a Montenegro that had hard won its independence at the end of the 19th century in spite of interference from neighbouring countries, at a time when Greater Serbia also became independent from the Ottoman Empire and shortly afterwards the Austro-Hungarian Empire proceeded to annex Bosnia Herzegovina. In short, the Montenegrins probably believed that they could boast a certain dignity in the family of small states that were gradually emerging from the crumbling of the great multinational empires, while at the same time developing a national consciousness that would lead them to be a valid interlocutor on the international scene. It is easy to see this in the avenue of the old diplomatic headquarters (Russian, English, French, Turkish, Italian), whose refined belle epoque structures evoke the urban allure that was probably breathed at the time. Nicholas I of Montenegro was in fact called the ‘father-in-law of Europe’, precisely because five of his daughters were given in marriage to European princes and rulers, Romanovs in the lead. An excellent instrument of diplomacy, hurray for human capital!

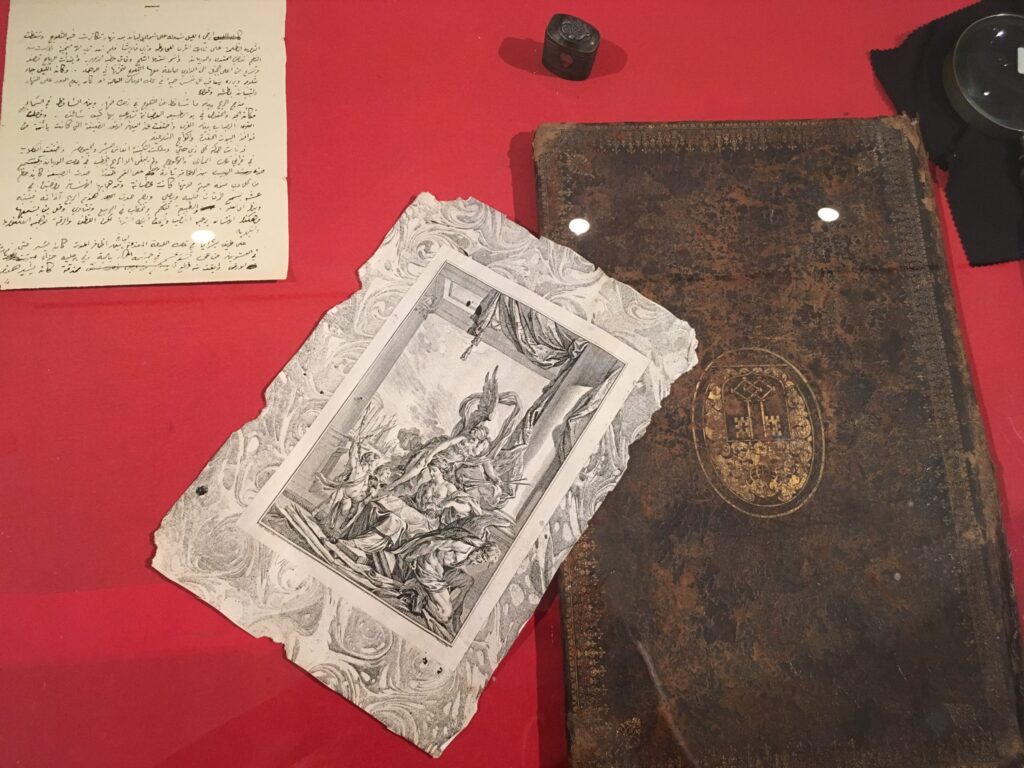

And this is where Italy comes in, when at the Royal Palace of Cetinje, essentially a cottage of more regal breath, I enter the room of Elena of Montenegro, former sovereign of the Kingdom of Italy, consort of Victor Emmanuel III.

It is in her room that I make the acquaintance of the museum director, an elderly lady with a bob, black fringes and lovely blue eyes, very courteous and enthusiastic. She knows Russian perfectly and we decide to communicate in this language, discovering that we share a veneration for Queen Mother Maria Fedorovna Romanova, whose portrait the palace displays in several rooms. It is, however, when I reveal that I am Italian that her eyes light up.

‘You know Miss, this is a kind of Casa Italia! Our Princess Elena did so much for your country, which we love! In Bari there is even a bust of her father, the ruler Nicholas I, they called him Uncle Nicolè. Until those villains drove him into exile in Antibes, in the 15-18 war. He never returned, bringing with him the sunset of the dream of Montenegrin independence’.

‘Well,’ I comment, ’what do you think about what happened next? After all, Mr Woodrow Wilson was very creative in inventing Yugoslavia at the Versailles conference’.

‘The annexation of Yugoslavia was a blow to all of us. The Montenegrins were not even invited to the conference and forced us to obey the crown of that Serb, His Majesty Karadordevic, a despot. All they cared about was that Greater Serbia dominated the Balkans. Only the Italians at that time tried to help by facilitating the landing of some 120 independence officers. But it did not work, and we plunged into a low-intensity civil war that lasted until 1924′.

‘And what role did Queen Helena play, assuming she played any?’

‘Did you see her at the Italian Embassy in Cetinje? All of us Montenegrins are grateful to that building. When the Italians invaded Yugoslavia in 1941, we welcomed them with open arms, we looked at them as liberators. We established the Montenegrin Council together and finally managed to regain our identity, the Montenegrin Kingdom was recreated and in personal union with the Kingdom of Italy’.

‘But how, wasn’t this in fact an occupation?’

‘Sure, but the years of 41-44 were the only years of intense Montenegrinisation of Serbs in our territory’

‘What a scary word!

‘You say. I, on the other hand, believe that everything would have proceeded for the best if it had always been the Italians and the cetnics who led us. The worst came after 8 September, when only the Nazis remained in Yugoslavia and the open and ferocious war began between the Germans and Tito’s communist partisans, supported by the Allies.’

‘I had always believed that the Yugoslav project had been deemed successful by the Balkan peoples.’

‘The Socialist Republic of Montenegro was a chapter in our History, perhaps a necessary one. However, the respect that our Montenegrin principality had proudly earned in the golden age of Nicholas I, the prestigious position that our country could boast within the family of European nations…soon it was all lost in the name of socialism and obfuscated by rampant Serbian nationalism.’

‘Again with these Serbs!’

‘Just think, dear, until 2006 we were still called Serbia and Montenegro. Only in the hands of that Dukanovic, a handsome man eh..to be precise! Very tall, like all Montenegrins, but a real schemer!..Well,I was saying! It was only thanks to him that we managed to obtain independence by referendum. Now it’s all to be written, we are a small, peaceful state, lacking in resources, but I assure you, so beautiful. And believe me, we will never forget what Italy has done for us.’

I still keep my misgivings. But is it appropriate to superimpose my superstructure on events that happened eighty years ago? Who knows. In the end, however, this is the opinion of a dear lady. What a story, though.

‘Give my regards to the Bel Paese dear lady, and remember to tell the stories of Montenegro to our Italian friends!’

And from Cetinje, Montenegro, that’s all, details of unexpected Italian micro-history included. A place that conceals under a pacifist Maya veil a firm pride of identity and independence, just as it has always done throughout its contemporary history. Small and determined, it once again enters the family of nations, no longer just European, but global.

Will it remain just a tourist destination of value and sophistication?

What will happen? Today, the country is fifteen years old and its history is young, yet to be written.

Ćao!