Pizzeria Veridiana, quartiere Jardins, São Paulo

Tudo acaba em pizza!, just as for Italians it all works out in tarallucci e vino. The waiter of Veridiana, an elegant eatery listed among the 10 best pizzerias in South America, explains this idyom to me. To dine in São Paulo, the third largest Italian city in the world, is to rediscover the flavors of the Italians who “came to make America” by reinterpreting flavors, replacing mozzarella with catupiry cheese, inventing calabresa (which I have never heard of in Calabria), applying the Brazilian slogan Beleza e grandeza even to the diameter of the pizza, exaggerated, festive, rich with different toppings. This is where rodizio was born, the concept of giropizza in front of which every Brazilian resolves business, family, life or death issues. Apparently, among the city’s 9,000 pizzerias, about a million are consumed daily, a true ritual, an existential comfort food that even deserves an ad hoc celebration on the recurring city holiday every July 10.

La Veridiana, however, is more than just a pizzeria. I have been staying for some time in the Jardins neighborhood, a very chic urban district between Avenida Paulista and Oscar Frere, where skyscrapers (arranha-ceus) and condominiums of sophisticated architecture have been built in a lush environment, which is why São Paulo likes to be known as the “tropical New York.” La Veridiana, like other trendy establishments in the neighborhood, gives me a chance to observe many Paulistanos, especially those who stop by the American bar before the rodizio. Just out their fitness at the nearby Club Athletico Paulistano, they reach the Veridiana and showcase their glamorous outfits, sip caipirinhas or a glass of Argentine wine near the caveu and the artificial waterway built in the magnificent interior patio. Design, elegance, fine-dining, excellent service. So unimpeachable does the world of nightlife in São Paulo seem at first glance, so incompatible with the free spirits of the Rio’s cariocas, true urban surfers, colorful in havajanas and in soul, happy to forgo Paulista perfection in order to enjoy every sunset in Ipanema and Copacabana until their last breath. “Paulista!” my former volleyball coach would yell this word at any inaccurate referees as an insult. A native of Rio de Janeiro, personification of the ancient feud between the two metropolises, he would tell me “don’t go Sao Paulo, gray city, ugly, dangerous. Rio city most bela do mondo, with Pao de Acucar, Leblon, Copacabana. Be careful there too, though.” Yes, many have told me that São Paulo is one of the most insecure cities in the world, where at his/her own risk any individual pulls out the cell phone in public places and orders on uber eats by uploading the passport, so that the delivery man can identify himself to the condo security officer. That’s what, at least, a Roman man from Eni’s São Paulo division tells me on a rain evening through the colonial streets of Paraty, on the road from Rio to Santos.

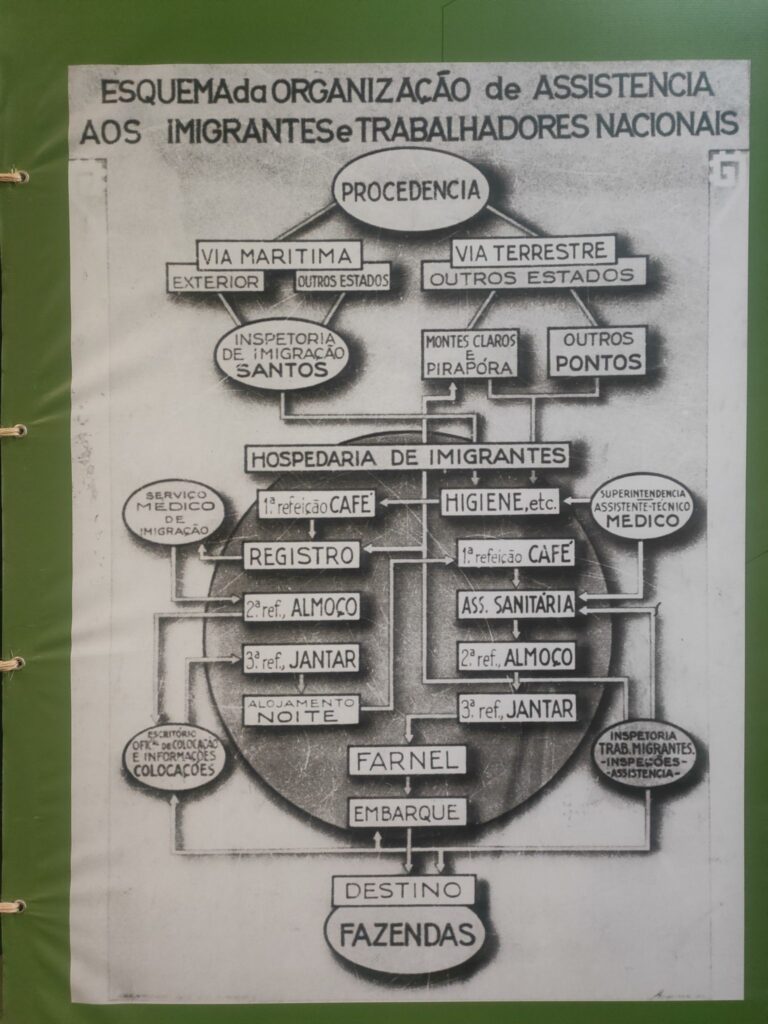

I came to São Paulo precisely to learn about the route of my Venetian ancestors, those who from the second half of the twentieth century docked in mass at the port of Santos, the thriving port of Coffee. From here they boarded the train to São Paulo, and arrived in the Bras neighborhood, at the Hospedaria dos Migrantes, also known today as the Memorial. It was a place of hope, of arrival, of disappointment, the Paulist Ellis Island. On the walls there are still Italian directions to the guesthouse and the cafeteria, whereas I read in the tablecloths magna che te fa bene! After a few days, sometimes months, they could leave for the fazendas and begin the coffee harvest. By 1850, the African slave trade had been abolished in Brazil, a backlash for the baroes do café, who had to recruit new labor abruptly. From the documents of the time, the fazendeiros described us as “great workers,” different from the Japanese immigrants who were “too different”. Perhaps that is why the Japanese devoted themselves to other things, starting with the streets around Praca da Libertade, still their today’s stronghold in the city. The Venetians exported polenta to Brazil, they spoke talian, a Venetian-Brazilian mixed language that introduced words like sopa, formaio, capeleti into everyday language, they gathered in the “San Marco Association,” until some left for Argentina and Uruguay with the first coffee crisis. In total, about 2 million people passed through the Hospedaria between 1887 and 1978, including Italians, Portuguese, Japanese, Koreans, Lebanese. In the museum lobby I meet a grandfather with his granddaughter. A genealogy student, she has come here to trace the path of her ancestors through the Memorial’s Digital Archive. I wonder how many and where mine are, I had once scouted out a large facebook group “I Zecchin in Brasil.” I think I will now visit the places of the Italians who decided to stay, those who in the early 2000s telenovela Terra Nostra helped create the imagery about Italian-Brazilians.

“Ubi italicus ibi Italia,” is the sign that greets all who enter the Italian Circle of São Paulo at the Italy Building. Saturday morning breakfast is a good time to run into the “Italians who have decided to stay,” many of them, habitually gathering in this space furnished in Milanese Art Nouveau style, amid objects inspired by the colors of the tricolor and vintage prints of Campari and Aperol Spritz aperitifs. Always devolved to the management of the Italian colony’s intellectuality, Il Cicolo Italiano has been a place of affiliation, Masonic meetings and often of protest. In 1924, Ambassador Attolico was welcomed right here to the sound of “Viva Matteotti!” (google for more historical insights). However, as much as the Italian lobby in Brazil had continued to represent the political currents of the Belpaese in anything but monochrome political affiliation, at the Terrazza Italia on the top floor of the Italian skyscraper it is possible to settle any differences, in a haute cuisine setting that provides the best 360-degree view in town. Instead, from the begninning a more informal Italian hangout has been the Girondino Café, not far from the Praca da Se, where the Cathedral stands. Here Italianinhos have always consumed the famous cafezinho paulista, although today Oscar Frere’s fashionable coffee roasteries offer tastings of Minas Gerais to Estato do Sao Paolo grains to more sophisticated palates in the industrial chic spaces of roasters Santo Grao and Suplicy.

Many of Italy’s great fortunes, however, were not only tied to coffee. São Paulo’s architecture tells stories. In the Centro district are the skyscrapers with the finest aesthetics:

the Farol of Santander and the Edifico do Banco do Estado do Paolo of lovely Art Nouveau decoration. Then, the Edificio Martinelli, named after that Lucchese entrepreneur. He was very tall for the time, he was 1.90m. He wanted to build the tallest skyscraper in Brazil, in all of South America, inspired by Chicago. For many years he held the record. Elsewhere, stands the Matarazzo Building, but which of the many Matarazzo’s building? This gentleman, Francesco Matarazzo, originally from Castellabate, was called the “second state of Brazil,” one of the richest men in the Americas. He arrived in Brazil with his wife and two children and began importing flour from the United States, going so far as to create the Industrie Riunite Francesco Matarazzo, which in 1936 became an empire of 285 metallurgical, textile and food plants with 20,730. He was the true star in the firmament of Italian entrepreneurship in Brazil, founder of the Palestra Italia soccer team (now Palmeiras), intermediary of Italian remittances to the motherland, philanthropist, powerful and intimidating to the old fazendeiros establishment of the Paulistas. Only three of his 12 children married members of the old coffee oligarchy (the first coffee plantations in Brazil seem to date back to 1750), all the rest were married to families in the mother country. The matrimonial question was certainly a caste issue, a field of heated competition in which the rampant foreign bourgeoisie measured itself against the holders of political power, the coffee lobbyists, the same ones who had their children graduate from the prestigious Faculty of Law in São Paulo’s Centro so that the judiciary could influence legislative processes and issue rulings that guaranteed the privilege and maintenance of the establishment.

However, the progressive fury of São Paulo continued to express itself, manifesting itself once again in the city’s architecture, in the layering of people, styles, trends. São Paulo is not only the city of elitism, of fashion, of fine dining, of glamour, of Oscar Nyemer’s Ibirapuera, of Aryton Senna, of PM Lula da Silva, who founded here the Partito do Trabalhadores, of which he is still the leader. To grasp the energy of São Paulo one must stroll down Avenida Paulista on Sunday mornings, when the Corso becomes all pedestrian and crowded with flash mobs, flea markets, spinning classes, coconut vendors, in front of a confusing and stimulating juxtaposition of styles in which the MASP, South America’s most important museum of classical and contemporary art, stands out. “Linear time is an invention of the West: time is not linear, it is a marvelous overlapping for which, at any instant, it is possible to select points and invent solutions, without beginning or end.” Words of Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian communist who trained in Gio Ponti’s Milan studio, later becoming the architect of MASP. She completed this building in 1968 with the intention of imposing a horizontal surprise to the vertical continuum of skyscrapers, in order to create a “free space,” a pause, a silence of a place of culture where art, men and museum were on the same level. He founded it with Pietro Bardi, an art critic and gallery owner close to the Fascist regime, who left the peninsula following the fall of Mussolini and later married Lina. With actress Nydia Licia, a Jewish woman from Trieste who fled racial laws in Brazil, and Assis Chateubriand, a Brazilian communications magnate, they devoted the rest of their lives in the Americas to the Masp. Through the window of the Masp, I continue to breathe in the energy of the city, which I find also in the colorful, unstructured, fallacious works of wonderful Brazilian figurative art, frequently inspired by the people and colours of the Amazon forest. Great prominence is given to women’s art, just as on the street I witness a feminist and lgbt+ procession, in line with the anti-machist and gender friendly rhetoric I also found in Rio. I would like to know more about this, whether this is really a brutally felt issue on a bipartisan level, or whether it is some kind of revanche against that Bolsonaro guy who slipped away in Florida at the defeat of the last election.

Actually, São Paulo is a metropolis of 20 million people, founded by Manuel da Nobrega’s Jesuits in 1554 on the land of the indigenous tupi-guarani, today gripped by the mourning for the death of Pope Francis (April 21, 2025), while being the richest and poorest city in Brazil, where the world’s largest gay parade takes place. A contradictory and unstable combination that can only engender a certain electricity, an anxiety of destiny, a messy projection into the future that makes it capitalist, dynamic at times frightening and straying, a true demographic and economic colossus worthy of BRICS membership. São Paulo must be explored extemporaneously, to be able to appreciate the casualness with which it was built, to be able to intercept what lies beyond the apparent Paulistanos snobbery, which will end of the day always envy Rio’s exoticism. If Rio’s beauty is visual, colorful, timeless, São Paulo represents the enterprise, the idea, the spirit of the bandeirante (pioneire), the ambition, like that of Martinelli, who wanted to build the tallest building of all. “Everything works here,” say the Paulistani. However, intellectual Nelson Rodrigues calls the Paulistano and to some extent the Brazilian himself an “upside-down narcissus.” He talks about the complexo de vira-lata (mongrel dog) complex, which originated in football but later expanded to the rest of the context. The Brazilian basically spits on his own image, finding no personal or historical pretexts for self-esteem.

Is it that true? I was told that São Paulogrew up in European historical thinking, always chasing the U.S. model. And to this day the city is still always running, despite the city’s transito, despite not knowing what model it is now aspiring to. But after all, in the waning moon of the West, is not Sao Paulo the expression of the existential question tormenting every major metropolis and country on the global landscape?

Then, after all, we are all Paulistas!