Tashkent Station, 8:30 AM It’s such a strange day, this one. I’m in Uzbekistan for work, and it seems I will soon get on a train that will take me to meet one of our clients. Destination? Samarkand. It sounds like a joke. Today I will find out if this legendary city truly exists. Early in the morning, at Tashkent station, the dry heat of the July steppe foretells a scorching travel day. I wonder if I will encounter the Samarkand of myth, if I will rediscover the languid, colorful, and fragrant atmospheres imagined in orientalist self-suggestion.

Passengers circulating through the hall snack on sunflower seeds, others take their seats piling up luggage and saddlebags, baskets of fabulous Uzbek bread, cartons of pomegranate juice, toys, and the iconic Alenka Muscovite chocolate bars. Once on the Afrosiyab train, the ‘tea lady’ wakes me up to give me a drink and hand me a packed snack offered by the railway company. After all, we are on the Silk Road; tea is a ritual, a rhythm, a contemplation.

In Samarkand, a driver with an unpronounceable name, friendly, slanted little eyes, and the usual raven fringe that is fashionable in these parts awaits me. Out of courtesy or custom, my local contact felt the need to have me escorted by a driver, as a ‘solo, non-Uzbek girl, our guest.’ However, I believe I can move around independently, and I suggest to the driver that we meet again in the late afternoon for a slice of melon. Getting around Samarkand is simple; it has an orthogonal urban layout, with paved parks and widespread caykhane (teahouses). Along the way, bread street vendors alternate with steaming samovars and the scent of doner, a brief summary of the country’s souls: caravan, post-Russian, Turanian, Arabic, timidly glancing towards the West. Although the city is now opening up to international tourism, Samarkand and its inhabitants still seem very traditional.

Here and there are gigantic statues that celebrate the personality cult of Tamerlane in a very Asian way, and further on, the gigantic statue dedicated to Islam Karimov, born and raised in Samarkand, the former satrap regent of the USSR Republic, who passed away in 2016. He left a controversial legacy, between resentment and nostalgia. Since Karimov’s death, the country has become the most populous of the ‘stans,’ one of the fastest-growing in the world, rich in mineral, energy, and agri-food resources, and finally open to foreign investment. Due to its strategic position, even though it falls into the category of landlocked countries, it is a subject of contention among the great powers competing in the renewed climate of the Great Game: Russia, Turkey, the EU, the United States, and China. Geopolitics aside, the true symbol of Samarkand’s history is the majestic Registan Square (‘place of sand’ in Farsi), dating back to the 15th century. The square in front is crowded with young brides, called kelin, who all look so serious. I ask someone: ‘Why?’ They kindly explain to me that it is local custom for the bride not to smile and to keep her head bowed so as not to reveal whether it is a marriage of love or an arranged one. I want to know more. I discover that in 2022 a survey conducted by the Uzbek Institute for Family and Women Research revealed that 39.9% of the interviewed couples married through sovchilik, a traditional matchmaking practice initiated by parents and other older relatives, while 33.9% married based on mutual interest. In 2019, the Family Code officially eradicated marriage under the age of 18.

However, families continue to arrange marriages through informal religious ceremonies, the nikah, without any local registration. The country’s opening to globalization has inevitably influenced the functioning of centuries-old family dynamics. The popularity of social media has made the prompt arrangement of marriages for daughters urgent, as they must traditionally marry as virgins. The danger that daughters may be exposed to the web increases the possibility of unspeakable dishonor for families, especially in rural areas. However, the conflict between modernity and tradition seems to be starting to heal. On April 30, 2023, Uzbeks voted by referendum in favor of reforming the Constitution, which establishes a legal, social, and secular state, and includes a package of amendments to the penal code criminalizing domestic violence and guaranteeing new protections for women and children.

Uzbekistan is currently ranked 94th on the Women Peace and Security Index, which evaluates 177 countries in terms of inclusion, justice, and security for women. The other day in Tashkent, the capital of the future, B was telling me about his marriage before hosting our staff in one of the trendy spots around Tashkent City Park, a futuristic sight. He married for the second time, and he seems happy about it. The first time he had to go deeply into debt to afford a wife; he had purchased a very expensive piece of jewelry, nothing compared to the luxury goods many of his peers have to invest in to show they can provide for their future bride. This affair practically ruined his life; he now has a little girl and is forced to pay the installments on the previous marriage pledge for life. ‘The fact is that now society is changing even in Uzbekistan,’ he says. ‘Although people still marry very young, more and more women are starting to work, jeopardizing the family mechanisms I’m telling you about. Everything that happened in the past now seems to be cracking. Sometimes we young men go into debt just to divorce shortly after, especially in the city, triggering a distressing vicious cycle.’

This is the millennial generation in Uzbekistan, caught between Islamic traditionalism and post-Soviet atheism. While embracing globalization, Uzbeks of my generation are trying to regain their identity after years of communism. Many of them are keen to point out that those seventy years of the regime devoured the local culture, and they say they are tired of foreign interference, although the feverish anxiety to conform to the Western model is palpable. And… when the so-called ‘free world’ encounters the cultural marker, anguish sets in. While the Uzbekistan of 2024 is buzzing with change and projecting itself into the future, Samarkand is real, right here in front of me, and its inhabitants sit comfortably in the inner courtyard of the palace. The men wear colorful crocheted Uzbek caps, and the women wrap their hair in soft fabrics. In the Registan courtyard, some sell carpets and fabrics in the former study halls of the madrasahs, others squat barefoot on large wooden benches to rest; some women sit on the ground with their daughters to display scarves, others drink tea on small terraces, or carve characteristic little wooden gnomes. Everyone minds their own business, placidly; when I cross their faces, they seem so imperturbable, at peace, it seems as if they are smiling, although in reality they are not. It’s as if there is an insurmountable barrier between me and them, despite how easy it is to receive their serenity. It is the adorable enigma of the Asian spirit. A boy later contradicts me at the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, telling me that even the great leaders of Central Asia actually had to contend with the most mundane human feelings.

It seems that it was Tamerlane’s beautiful Chinese wife who ordered the construction of this architectural jewel during her husband’s absence. Accidentally, the appointed architect fell in love with her. Tamerlane quickly had him executed upon his return, imposing on all women to wear the veil so that men could not fall into temptation.

I reflect on how many cultural similarities have survived until today while visiting the most impressive and singular monument of Samarkand, the Shah-i-Zinda, ‘the tomb of the living king,’ a necropolis of incredible craftsmanship, a marvel of turquoise tiles, terracotta, and majolica where one of Muhammad’s cousins is also believed to be buried. It is an unforgettable, silent, spiritual place where it is possible to reconnect with a more ascetic dimension, at the end of which one reaches the Samarkand cemetery, a fascinating park to walk through and discover the curious frames of the last century, of the Uzbeks who were.

Before returning to the city, I venture into the old and quiet core of Samarkand, a tangle of unmapped, identical, crooked, closed streets, and I confess to feeling some apprehension.

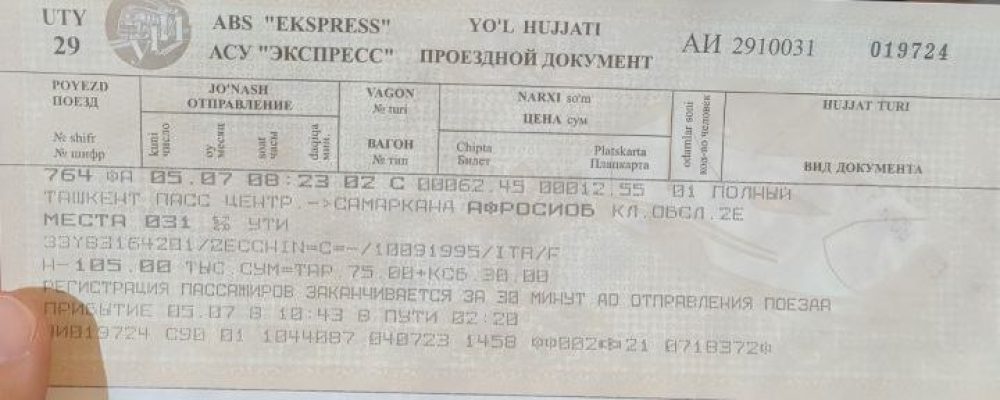

Tashkent-Samarkand Train

I stumble upon the city’s Sephardic and Ashkenazi synagogues by chance, when an elderly gentleman invites me to visit his courtyard, where a series of delightful trinkets are piled up (glasses, plates, busts of Lenin and other Soviet leaders, carpets). Then I meet a sweet lady who is hanging out laundry; in Russian, she asks me where I come from, smiling adorably when I tell her I am Italian, without fear of letting me glimpse her complicated set of teeth. I am late for my meeting with the driver from the morning, for that promised feast of incredibly sweet melon on the way back to the station. Before saying goodbye, he wants to show me the place that makes the inhabitants of Samarkand most proud: the tomb of Tamerlane. It is worth it. When I cross the monumental entrance, I am immersed in the absolute and respectful silence of the mausoleum, whose interiors are embellished with deep niches decorated with muqarnas, plasterwork, and high reliefs covered in gold. The gold is prevalent, never exaggerated; it envelops me with a strong sense of royalty and solemn hieraticism. Anyone who tries to violate it could be punished: on Tamerlane’s tomb, I read an inscription: Whoever violates my peace in this life or the next shall be subjected to inevitable punishment and misery. Wow, I think Tamerlane has cast a spell on me. I must hurry; I will be late for the last train to Tashkent. Taking the train means granting yourself the necessary time, watching the landscapes parade by and the stations come alive, observing the people you travel with and yourself, rocked by the suspensions. Across from me is a French couple, father and son, commenting on the extraordinary day they had in Samarkand. In the rest of the carriage, there are only Uzbeks, who even have takeaway tea bricks, as if the one from the ‘tea lady’ wasn’t enough. The daylight is fading, and there is no better moment to surrender to the steppe, yellow, ochre, faint, uniform… so flat as to elicit the most tangled thoughts, almost as if that boundless space were waiting to be filled with the content and thoughts of a young intruder who happened upon the eternal city of Samarkand on any given day, existing, lingering, disappearing, without becoming a part of it.