Every day at 11 o’clock, the only private company that takes visitors to David Gareja, the ‘Gareji Line’, leaves from Freedom Square. I had spotted the vehicle through forums on Facebook and Tripadvisor. No reservations were needed, just show up at roll call. A tour operator had collected 25 lari each for the entire round trip. There were about 30 of us brave enough to gather at the shady morning meeting, all of us under 40, and we would then be divided into two shuttles. A two-and-a-half hour drive to the Azerbaijani border awaited us. We began to glimpse the end of our journey as the urban settlements gradually gave way to hilly, green, uninhabited territory. The road was still paved when we stopped to admire a huge valley whose end we could not see, an endless expanse of grassland that faded into the distance of the plateau. From there on, the hills would change into beaten terrain, potholes, steep paths, arid clearings, gradually becoming more and more deserted, until they became cyclopean canyons.

It was not a comfortable journey, but certainly a scenic one. To conquer the visit to David Gareja, the traveller is called upon to overcome a winding path, oblivious of civilisation, at the mercy of the most parched and inhospitable nature. Finally, we had arrived. David Gareja is a Georgian Orthodox monastic complex carved into the rock, located in the region of Kacheatia (eastern Georgia), on the semi-desert slopes of Mount Gareja. It is named after David, one of the thirteen ‘Syrian fathers’ who came to Georgia in the 6th century to develop monasticism after the conversion of the area to Christianity, when Zoroastrianism and animism were still widely professed. The complex includes the ‘Lavra Monastery’ and the ‘Udabno Monastery’. The former is located within the Georgian borders, and is still inhabited by six solitary monks who lead an ascetic life among chapels, refectories and rock-cut cells. The Udabno complex, on the other hand, lies in limbo between Georgia and Azerbaijan due to a sketchy Soviet-era geographical determination, and is therefore the subject of dispute between the two countries. A rusty railing still demarcates the border, so access to all the rock churches is not always guaranteed.

The sign simply indicated Udabno, without suggesting which would be the best path to climb to reach the summit of Mount Gareja. Backpack on our shoulders, sun in our faces, legs and arms at work, we started to climb. No safety measures, no protection, just lots of hard work, sun and the goal of reaching the summit, hoping to avoid the Caucasian snakes. It took about an hour and a half of more or less impassable climbing to pass the forest and approach the glade that would lead us to the summit. Every now and then we would meet some fellow climber, who would suggest a route, who would urge us to continue because it would be worth it. Not many had reached the goal, only the most convinced souls. That is why Mount Gareja is something singular. It only belongs to a select few ‘pilgrims’ who are willing to raise their souls above these endless landscapes, ventilating them with the taste of eternity. We were up there. A votive chapel awaited us in its presence, along with three Georgian soldiers.

Behind us the canyons of Georgia more or less brushed with green glades, in front of us a metaphysical, parched, Azerbaijani steppe. It was so boundless and deafening that I felt like disturbing it, to realise how unconcerned that slice of nature was in its immortality. So I started shouting my companion’s surname at the top of my lungs, and the steppe answered me with its echo. I loved that place! Very much so, and I was happy to have won that climb.

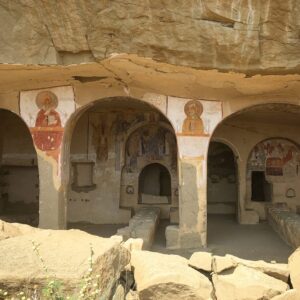

And descending steeply towards Azerbaijan, there, forgotten by history and time, stood the hermit caves of David Gareja, dusty, abandoned. No noise, no scent, just the pacing of my steps. On the other hand, there are still some nights in which I feel the terrible memory of the fear I experienced for an instant in front of the precipice where I was walking. In fact, I could have rolled down at any moment for the slightest carelessness, or for the arrogance of wanting to reach even the most remote and unreachable cave. In centuries past, these churches were the centre of Georgia’s spiritual life and a reference point for sacred art. The monastic complex flourished between the 11th and 13th centuries, when it was inhabited by some 5000 monks. During the Mongol and later Persian invasion (1615), the territory was devastated and 6000 monks were executed on the orders of Shah Abbas. In Soviet times David Gareja was used as a military training site until 1998.

The frescoes I could see in front of me had never seen a touch-up or restoration, they simply stood there, beautiful and vivid, as if the faithful of the past had been gone for a few minutes. I felt the power of faith. Of a faith that had never belonged to me, but whose intensity moved me. A few centuries ago someone had come here to worship their God, in the sun of the day and the darkness of the night, in the silence of the mountains, in the austerity of nature, in the noble grandeur of this undisturbed corner of the world.

Even today, I still feel the emotion of those lost moments in the Caucasus, of when I was able to touch a hundred-year-old fresco just like my distant predecessor. Because the extraordinariness of that place was precisely this: the feeling that we humans could pass the baton from one edge of history to the other, fortuitously returning to the same remote place, overcome by the same beauty of the frescoes, without the intermediation of time, of progress, of anyone. And for a moment being able to ignore the passing of time, in the presence of the same unchanging steppe. That’s why I thought that each of us belonged to David Gareja, that in days choked by banality I should think of places like this to remember how lucky I was to be part of all this, it was surely one of the most extraordinary places I had ever seen.

The bus was calling, and we had an hour’s walk downhill so as not to miss the ride. So we said goodbye. Before heading back to Tbilisi, the bus stopped in a small village in the middle of the desert, and we slipped into the first bar, exhausted and happy, just in time for some Georgians to give us three mugs of Natakhtari beer, just because ‘we were Italian’.

An unforgettable day was matched by an unforgettable dinner, at the ‘Maspindzelo’ restaurant in Tbilisi, a historic restaurant with traditional cuisine not far from the Hammam. At last we could taste all the Georgian specialities in one evening, khachapuri, stewed meat, roast meat, salad with walnut sauce, shashlik, and a plate of khinkhali (dumplings) with mushrooms, meat and vegetables. ‘Dumplings are only eaten with the hands’, say Georgians, and if you ‘eat the hat too’ ‘it’s bad luck’. Superstition aside, khinkhali are so beloved that they are practically the symbol of the country, not surprisingly the iconic magnet in souvenir shops tends to be a giant dumpling.

My second Georgian adventure could only end at the table, the best way to toast a country that had given me so much in such a short time, enchanting me with its soul, its present, and its past. We said goodbye to Georgia the next day, in my heart hoping not to return too soon, just to preserve the magic that had struck me the first time I had seen it. Nachvamdis!