Every day five o’clock tea is served on the deck, here in the Nile motor ship. Greeks chat until evening time, Italians sunbathe in their bikini, even some Germans pop up, otherwise why would there be Linz cake at the cruise buffet? We are all sleepwalking, floating in a warm, muffled atmosphere, after a sleepless night and a scorching visit to the Valley of the Kings, at the time of Karnak and Luxor. ‘Wake up at 4.30am,’ Ahmed, our guide, had told us the night before at Luxor airport.

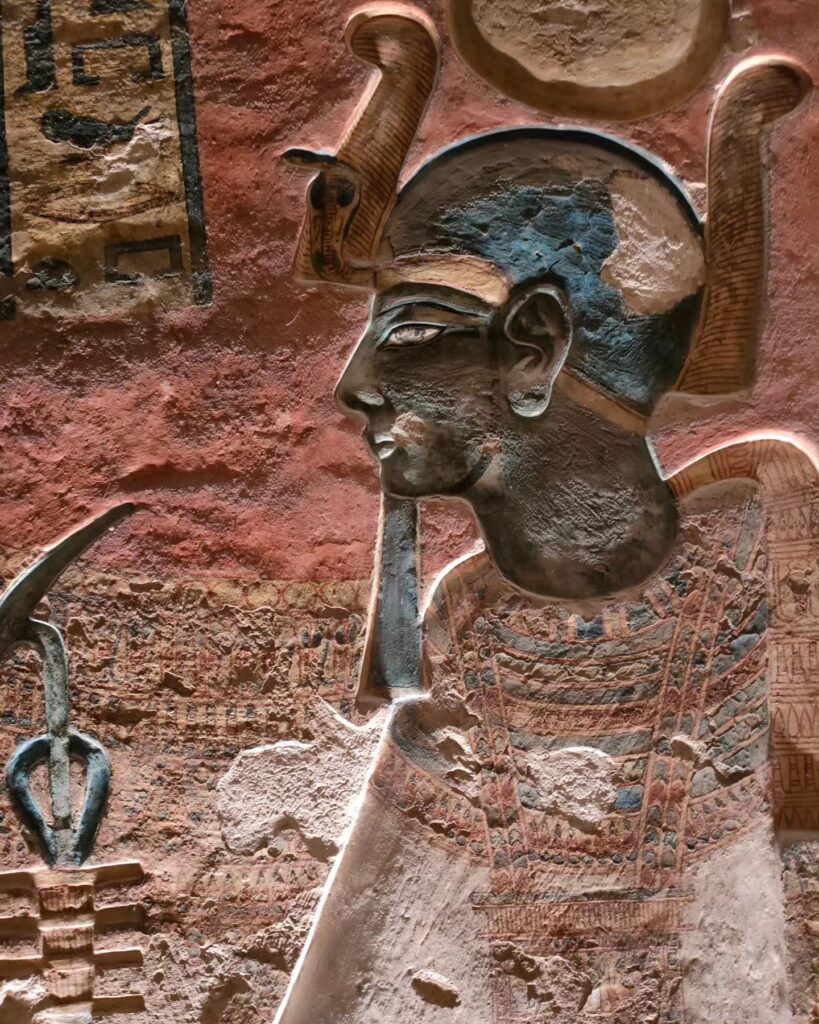

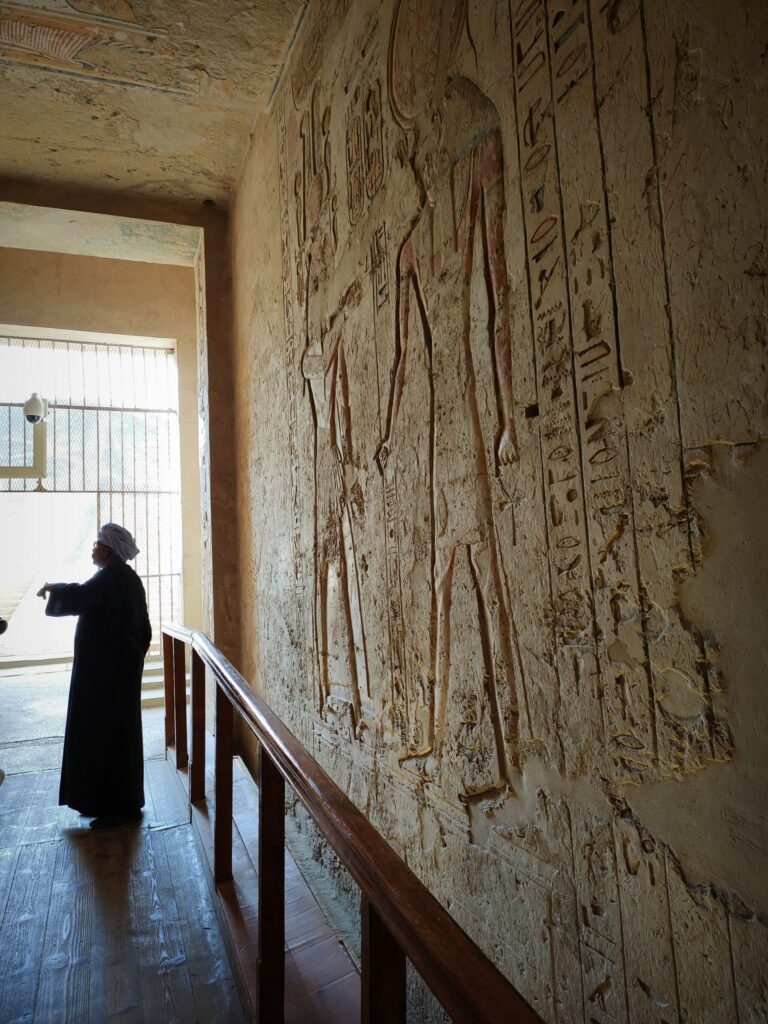

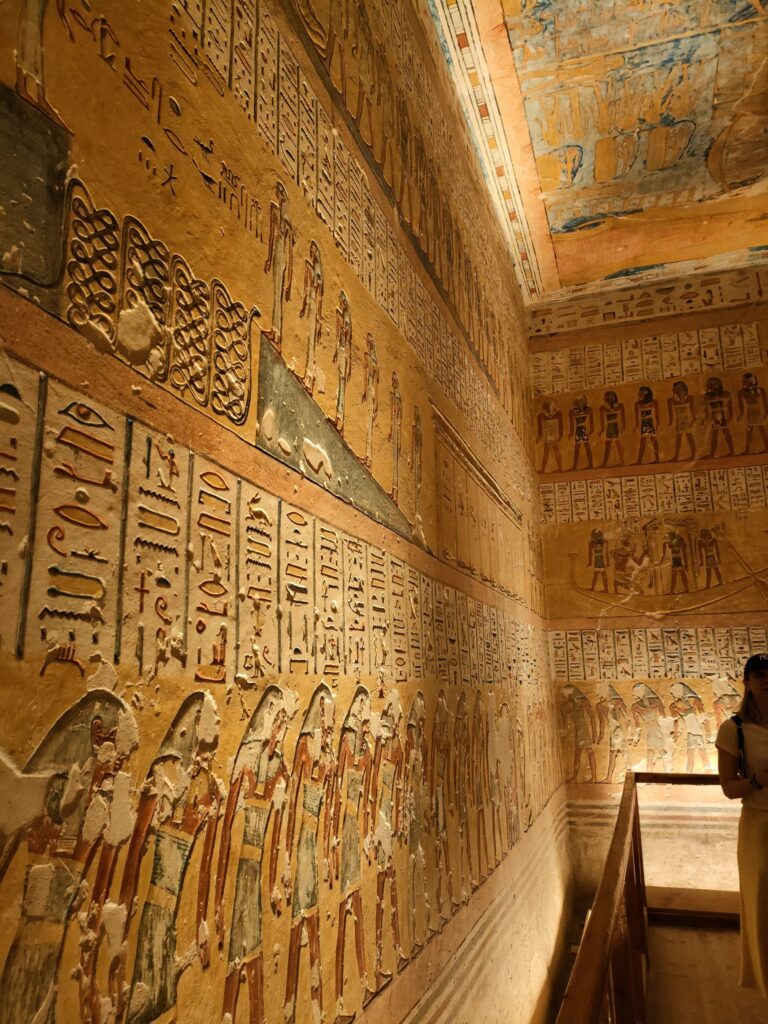

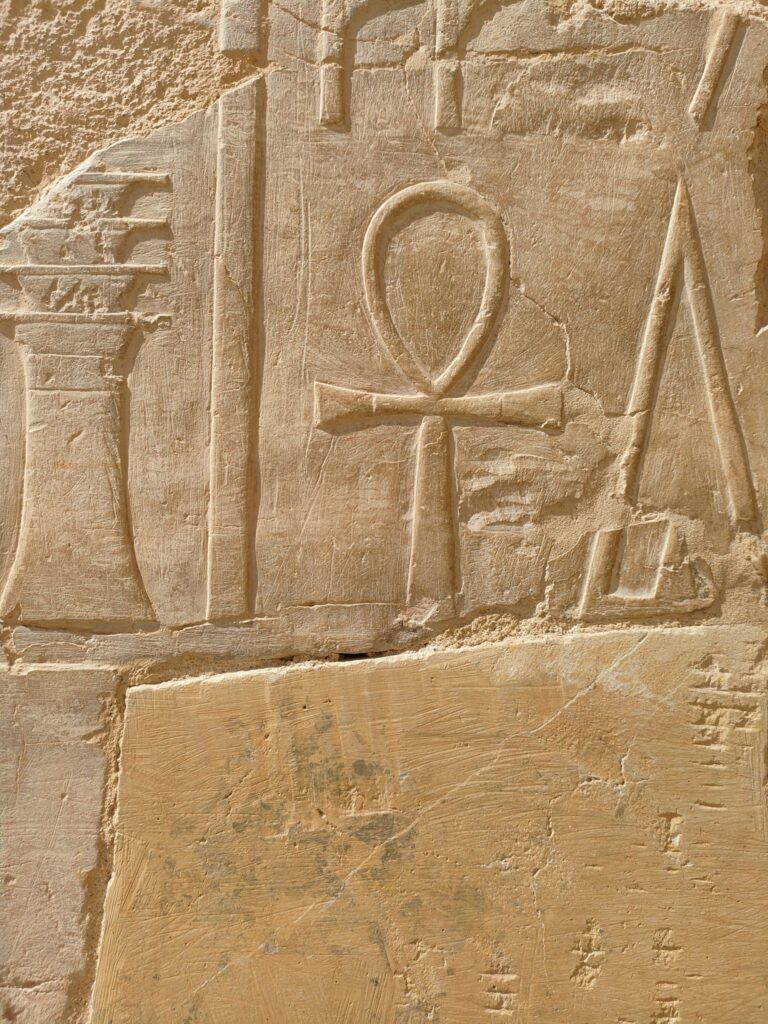

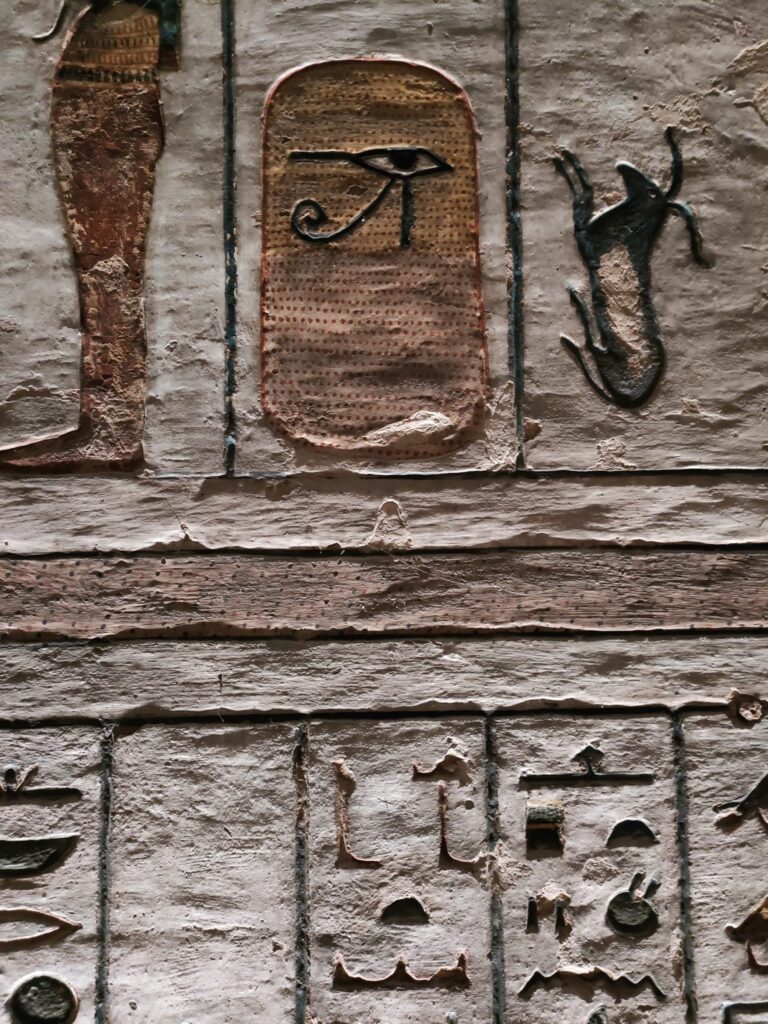

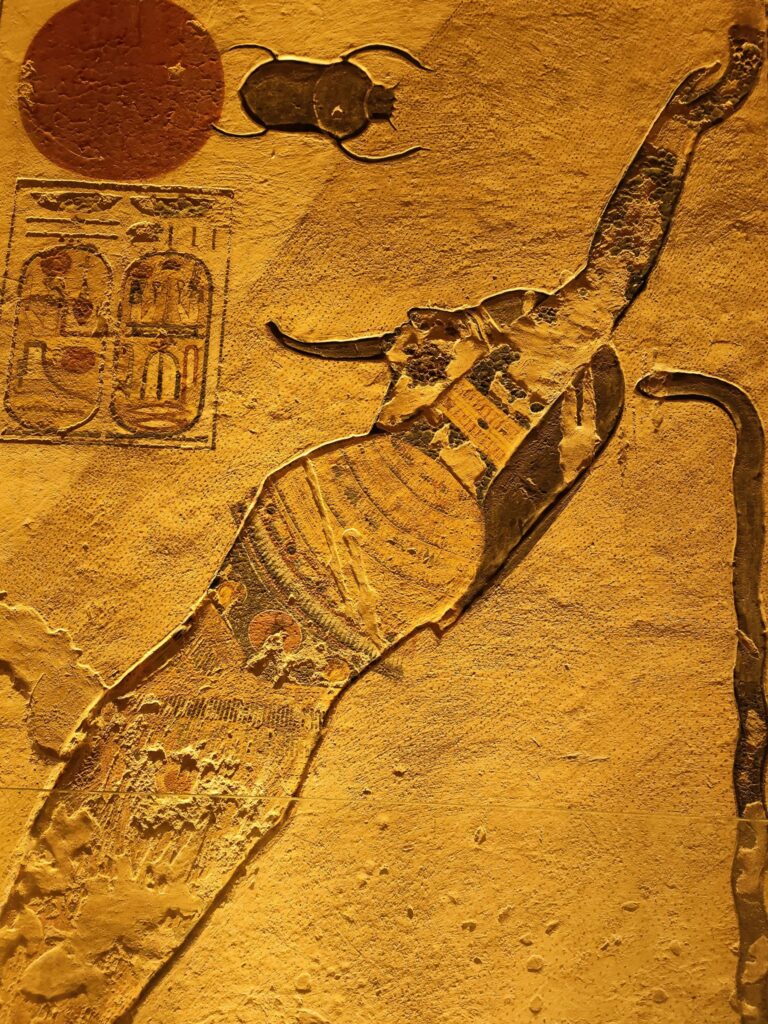

Upon last night arrival at the pier, the Egyptians had set up a buffet of sandwiches and fruit for the new passengers in the middle of the night. A few hours later we were on the western bank of the Lower Nile, where the sun sets, and so do the souls of Egypt’s pharaohs, buried there. Egyptologists, archaeologists, and art looters unearthed some sixty-five of these monumental underground tombs between the 19th and 20th centuries, when Ottoman Egypt, still in its nonchalant stupor, was unaware of its magnificent past. If in our imagination the discovery of Tutankhamun’s intact tomb (1922) helped to shroud the history of this thousand-year-old civilisation in legend, I wonder how many treasures and discoveries remain silent and buried in the desert sands, perhaps for eternity, as evoked by the fascinating symbolism of the “ankh/ key of life”. Keys, beetles, hawks, jackals and papyri… the Egyptians entrusted their divine rulers to the world of the Dead, preserving their organs in canopic jars, trusting in the protection of sacred animals, the same animals that inhabited the fertile region of the Nile, where water gave life, grain, the wealth of the Egyptian empire. What remains today of the Egyptian granary? It would turn over in its sarcophagus Queen Hatshepsut, the first ruler of ancient Egypt to reign as a man, with the full authority of the pharaoh. The same one who, by making herself portrayed as a male ruler, had subverted the rigid patrilinearity of power, consecrating herself to the memory of the ages in her gigantic temple, muffled by todays inglorious Polish restoration.

Nothing compared to the staircase of the Colossi of Memnon, which Giovan Battista Belzoni already recounted in his memoirs. Aside from the dingy streets of Luxor and alabaster shacks of dubious originality, these incredible sculptured individuals loom on the horizon, reducing the human beings in the vicinity to a miserable anthill. Not much different from the feeling that Egyptian subjects might have had in ancient times, when they proceeded across a 1.7 km paved with sphinxes, to reach the temple of Karnak after their visit to Luxor.

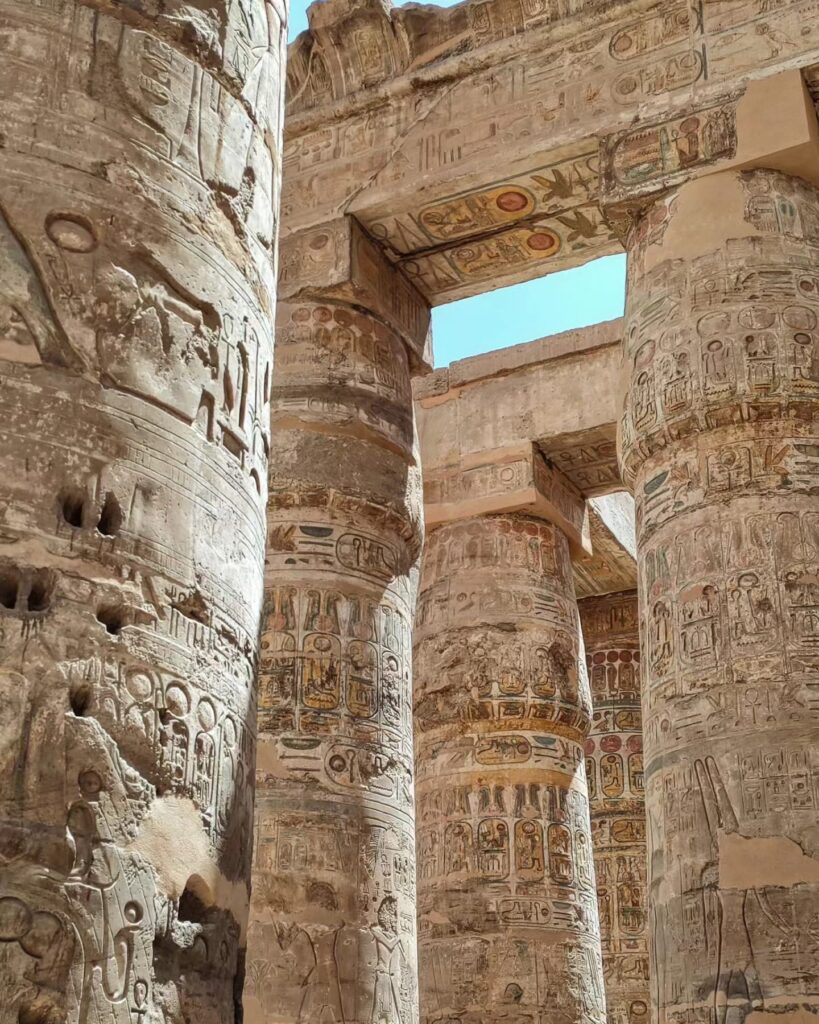

Today in Luxor the Eid of Ramadan begins, almost the entire city spills out into the main squares, along the river. It was the Europeans to give this place the name Luxor, bequeathing it a few buildings, first and foremost the Winter Palace. Today, many boys and children approach us asking for a photo, tips, munching on snacks, offering to lead us to the temples. Instead, we are escorted by an armed plainclothes officer to our points of interest. The reality contrasts sharply with the inestimable value of the temple of Karnak, a kind of seminary for 70,000 priests in Ancient Egypt, whose majestic colonnades I will always remember. This was the symbol of Egypt’s glorious past, the only one possible, or so said Ahmed.

The invasions of the ‘Asiatic peoples’ (the ones he meant coming from Mesopotamia, i.e. the Assyrians) in the 7th century BC, the Hellenistic Ptolemaic period and finally the period of Roman domination are historiographically narrated in Egypt under the chapter ‘occupation’. Occupation, specifically, which is supposed to have last until the coup of the Free Officers in 1952, following which the (ubiquitous) British presence ceased. A curious narration of the course of history, which only recognises its identity in the era of Pharaonic hegemony, watering down the richness and scope of events in between. Even today, Egyptians consider themselves descendants of the civilisation of the pharaohs, albeit uncertain when asked to confer the same genetic inheritance to those they contemptuously refer to as saida, (southern agricultural peoples), who in any case have nothing to do with the Nubians, dark-skinned African minority groups. Moreover, Egyptians struggle to fit precisely into the signs and meanings of ‘Arab’ ethnicity. Controversial, for the country where the Arab League has established its headquarters, and where Gemal Abdel Nasser founded the pan-Arab movement.

It seems to me that the only immutable witness of this people is instead the Nile. Almost like a deity personified, this cool, generous and majestic watercourse flows slowly and placidly through the whole of Egypt, from the Mediterranean Sea to Ethiopia, determining the fate of the land it bathes, for better or for worse. Also of the two tablecloth sellers who hurriedly dock our motorboat, trying in Spanish, Italian and German to throw goods at us, at clearly exorbitant prices. The Greeks shout ‘Pirates, pirates!’ and then buy amused. I go down to dinner, the bread is very good and there is always the dish of the day, whether it is a roast meat or fish, the chef knows it all. Then well, I can’t wait to bite into my chocolate marquiz, I don’t really know what that means, and it’s nothing heavenly, only here it actually seems to be the best dessert I’ve ever tasted, I’ll set aside a small plate every night.