1.30 p.m., Beeka Valley

‘And now…our 2017 Reserve du Couvent red!’. One after the other, we had tasted the signature bottles of the iconic Chateau Ksara: in addition to the red wine, a 2016 Blanc de Blancs, a 2018 Sunset rosé and finally a Moscatel.

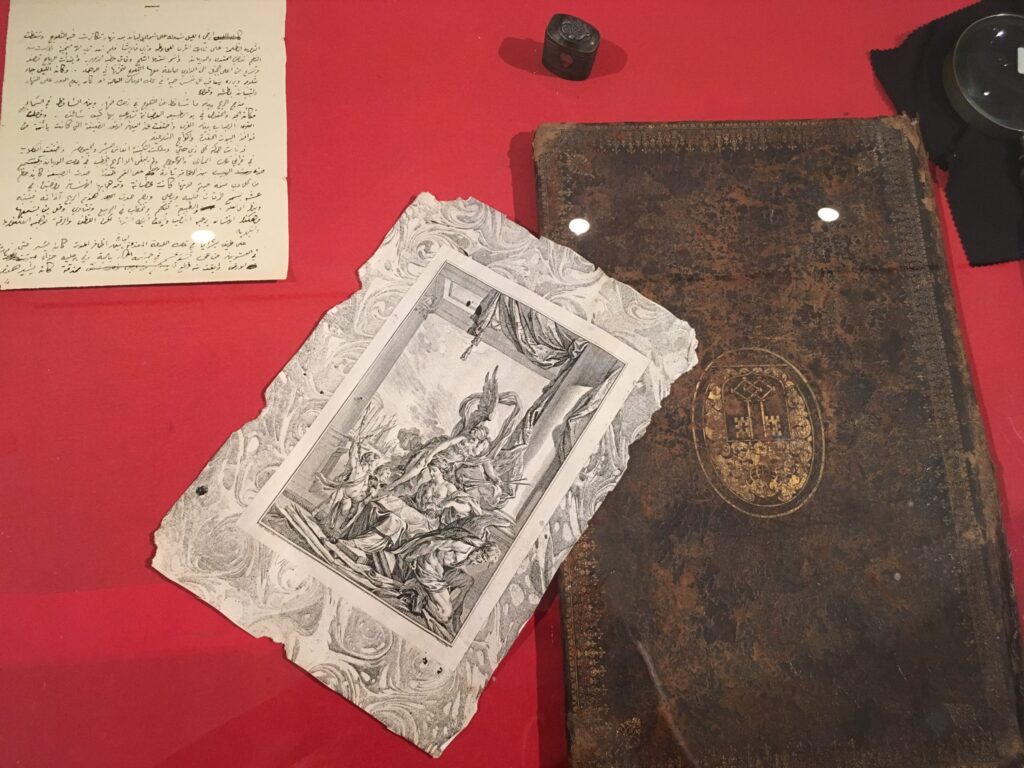

Founded in 1875 by Algerian Jesuits, Chateau Ksara now produces more than 2 million bottles, whose 50% reach the foreign market, particularly the UK. Coming from the most flourishing French colony, the Algerian Jesuits initially planted these vines in the area of Zahle, the largest city in the Beeka Valley. However, the origin of their cultivation is still shrouded in legend today: Noah (whose tomb is said to be in the Mosque of Kerak) is said to have planted the first vine here, or that it was some orphans taken in at the Chateau Ksara monastery, or a hunter, who discovered the ancient underground caves dating back to Roman times (2 km), in which, thanks to the exceptional temperature and humidity conditions, barrels and bottles are still stored and preserved. An impregnable set-up, surviving the instability of the civil war, which has consecrated the Chateau as a myth of Lebanese resistance and greatness. A national icon.

The Beeka Valley is a narrow plateau between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges (bordering Syria), tempered by the nearby influence of the Mediterranean. A microclimate that guarantees a high temperature range, which seems to be the secret of the quality of these grapes. In fact, Lebanese friends had laughed the first evening in Beirut when we had said we wanted to go as far as Beeka. Oriana Fallaci had already explained the reason, quoting a nursery rhyme in her Insciallah: ‘My haschish doesn’t hurt/it’s good stuff, it comes from the Beeka/ from the green valleys of Baalkbek/and it’s cheap.’ Indeed, according to estimates reported by the Independent’s great correspondent Robert Fisk, the wealth of the Beeka soil is capable of yielding some 10,000 tonnes of haschish a year, fuelling a racket involving the entire Middle Eastern trade. Nevertheless, even at the time of Fisk’s The Great War for Civilisation, The Conquest of the Middle East, this area bordering Syria appeared very poor and inhospitable.

We were in the Beeka by a series of fortuitous events, as always.

That morning Y. Hussein would never arrive at our hostel, nor would his phone ever ring to my numerous calls. As chance would have it, we stumbled upon a nerdy guy the night before, there in the hostel dormitory lobby. He was a young British history teacher, too engrossed in wanting to complete the most orientalist trip of his life at all costs to understand anything about it. Together with his girlfriend from Munster and her third-willing friend from Cologne they were staying in our Saifi Urban Garden, arriving from Jordan, from the coveted excursion to Wadi Rum. They were only staying in Lebanon for three days, then the guy would continue on to who knows where with the aim of arriving in India. In any case, we had deduced from our nightly conversation that they would be travelling to Baalbek the next day, that was what interested me. Like every “beirutiful” morning of that trip, I woke up very early, trying to figure out how I could assemble the itinerary I had prepared. I went to call the gang of three, I had made it through. As Mari reached me later, she looked at me incredulously and fresh from her extra hour and a half of rest: after negotiating the itinerary I had prefigured, a private shuttle organised by my trusty receptionist would take us up Mount Lebanon, taking us to Beiteddine-Chateu Ksara-Baalbek. We set off, with that English idiot who was going to bawl us out with loud music for about two hours of the journey. That was how we ended up in Beeka, sharing our journey with three guys, a driver, bad music, but at least an affordable price of about $35 each for the whole tour.

Delayed in our schedule, we were forced to miss Deir El Qmar, the only surviving medieval city in Lebanon’s Shuf region. We were only passing through, just enough to notice the warm honey-coloured sandstone lining old Ottoman khans and churches.

Since the late 18th century, Christians and Druze had coexisted peacefully here until the clash of 1860 and the conflicts of the last century. While for generations Christian-Maronite schools had been attended by pupils of both denominations, then came the Mountain War (1982), in which Phalangists and Druze fought fiercely against each other. By the end of the war, Christians had dwindled from 5000 to 1000, so Deir El Qmar remained a Druze stronghold. However, in recent times, Druze have started to attend Christian churches again, just as they once did, as documented by the traveller William Darlymple in his Sacred Mountain. A testimony to the fact that, in this part of the world, despite all the difficulties, religion has not always driven people away, but often brought them closer together.

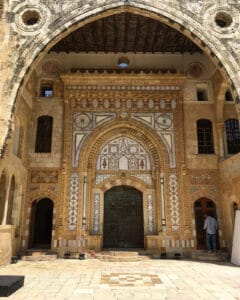

On the opposite side of the valley stood our first destination, the Beiteddine Palace. At the entrance there were still posters of the Beiteddine Art festival in July, with a giant picture of the event’s godfather, Gerard Depardieu. Rising among the valleys of the Druze, Beit-ed-dine means ‘house of faith’, recalling the Druze hermitage that stood on the ground of the present palace. It was Emir Bechir II Chebab who commissioned the construction of the so-called ‘Lebanese Alhambra’ in the early 19th century, thanks to the valuable contribution of Italian architects and Syrian craftsmen.

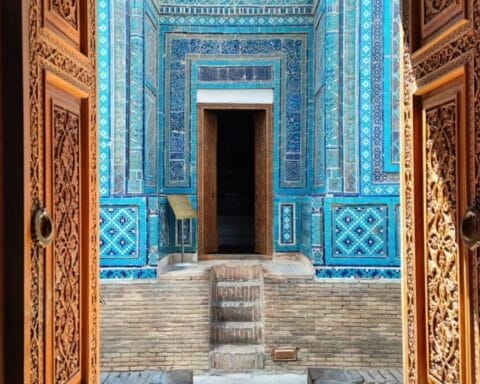

Later the seat of the Ottoman governorate, then of the French, and finally the summer residence of the President of the Republic of the Cedars since 1943, the magnificent palace reminded me of the ancient riads of the grand viziers in the medina of Marrakech, albeit set in a far more idyllic context, ventilated by the coolness of the mountain vegetation and embellished by lush gardens. 90% defaced during the first Israeli-Lebanese war (1982), the palace was rescued by Druze billionaire leader Walid Jumblatt, who ordered its restoration in 1984, returning it to the government in 1999. In addition to the exquisite handcrafted carvings of the samlik (reception hall) and the hammam, modelled on the style of Damascene stately homes, the museum now holds a unique collection of Byzantine floor mosaics dating back to the 6th century AD, mostly from Jiyyeh, 30 km south of Beirut, and brought here by Jumblatt himself in 1982. Beiteddine was certainly the best architectural complex I had seen so far in the Lebanese journey, but we soon left its rooms, its cypress and cedar trees that had invited us to brief contemplation.

Once we had caught up with the silly Englishman, who was overactive in showing off interest in every imperceptible detail, we were on our way again. We were finally on our way to Baalbek, ancient Heliopolis, the city of the sun. Opium aside, the poverty of those areas had in the past favoured the conversion of the Shia peasants of Beeka into valiant followers of the ideology of the Iranian Revolution. Following the civil war, the Ayatollah’s Revolutionary Guards, with tacit Syrian approval, evicted the government army from Baalbek and hoisted the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran over the ruins of the Roman Temple, becoming the centre of anti-Christian militancy. Hezbollah or Ayatollah signs still reign in Baalbek’s main buildings next to the Dome of the Rock, or posters depicting women wrapped in thick black chadors. According to Darlymple’s sources, it was certainly in Baalbek that the bombing of the American Embassy in Tehran was planned (1979), and it was here that many of the hostages were moved and kept.

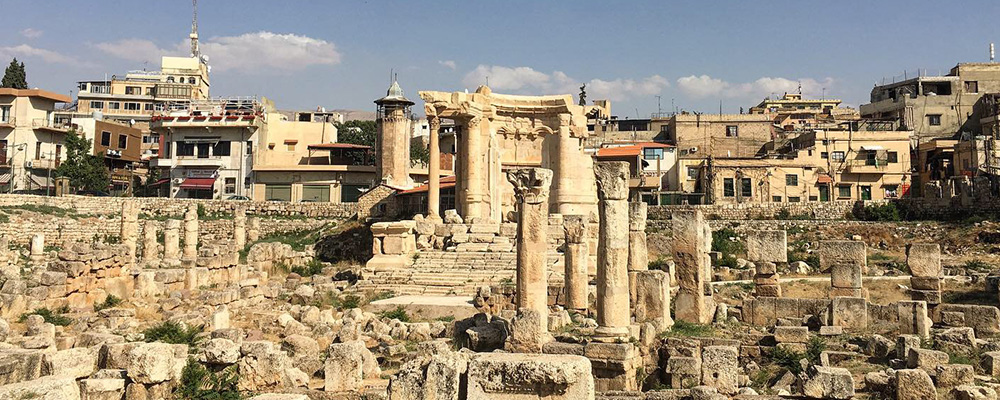

Exactly here, in the middle of the shacks and next to a small historic centre, stand the ruins of the Temple of the Sun. Having abandoned our companions, who suggested a lunch break through a packet of chips at the entrance to the site, we gotlost in the narrow streets of Baalbek’s shacks. Entering a patio through a small doorway, we spotted a table laid. We would visit the temple only after lounging here, at the Baalbek Guest House, an oasis of peace where we refreshed our jaws with juicy prickly pears and hummus.

The Temple

Climbing up the propylaea, more or less blinded by the sunlight, as if we were ascending the Elysian Fields, we were at the site of Heliopolis. Facing the baroque orgy of its ruins, I was overwhelmed by the grandeur. The columns, each almost two and a half metres in diameter, were the tallest in the classical world. It was a monument of great scenic impact, theatrical, overly decorative, opulent, an example of formidable Roman propaganda skills, conceived more for ostentation than religiosity. However, Heliopolis long represented a stronghold of paganism, to the point that Justinian had to order the destruction of its temples (Temple of Jupiter, Bacchus, Venus) and forcibly convert pagans to baptism, on pain of exile and confiscation of property. To ensure that the temple was not rebuilt, the Byzantine emperor ordered eight columns of the Temple of Jupiter to be transferred to Byzantium, there in the centre of the Hagia Sophia basilica. Nevertheless, at the end of the 6th century, when the Byzantine monk John Moschus visited these places, Baalbek was still the stronghold of impiety, where the pagans who had survived the numerous purges continued to persecute Christians. Not even the basilica they built at the centre of the temple of Bacchus, in a desperate attempt to suppress the militant pagans, remains of the Byzantines. It seems that French settlers deliberately removed it for pure archaeological dirigisme. Nevertheless, this site has survived it all, plundered and occupied by Umayyads, Byzantines, Ottomans, French, torn apart by interminable conflicts. Most of all, the Temple of Bacchus, built under the empire of Antoninus Pius, has survived.

Of the Temple of Jupiter, the largest temple in the ancient world, only the monoliths of the ‘Trilithon’ basement remain, weighing 1,200 tonnes each, the most imposing ever to have existed, on the nature and origin of which the investigation of archaeology still hangs. At the site of Baalbek (from Bel, the sun god of the Canaanites) everything is of disproportionate size, so immeasurable as to intimidate and pervade the viewer with a kind of magnificent and boundless vastness. One feels so lowly in front of such limitless beauty, it almost seems as if one cannot touch and walk on the mammoth stones of Bacchus’ time, although the earthiness of the restorers working in front of me reminded me that such hieraticity could be violated.

That late afternoon we would pass out in our sleep on the return journey, tired and sweaty, it was very hot.

In any case, I was beginning to feel the fatigue, the daily grind and the delirious logistics of those days were starting to get to me. In the evening, we would seek the comfort zone in Mar Mikhael dining at Seza, the Armenian tavern that had welcomed us the first night in Beirut. Perhaps the worst dinner of our trip, which we would complete with an ibrik coffee strictly with cardamom, on the colourful steps of Achrafieh. There we would plan our last day of adventures in Lebanon.