Fiumicino Airport, Rome, 8 a.m.

“A jam croissant and a soy cappuccino, please”. The last lactose-free one, I think, craving the huge and creamy maritozzo in front of me, cursing my intolerances. Groggy from the night at the airport in Venice, having landed at dawn in the intercontinental flight terminal at Fiumicino, I try to answer, still on an empty stomach, in a foul mood, the question everyone has asked me: “But why Tunisia?”

I think, perhaps, that I told myself that I wanted to cross this 100 km arm of the sea, which separates Sicily from the African continent, to know, to see, what lay beyond. How many similarities, what differences? What insurmountable misunderstandings of geography and history have condemned two riparian countries, just an hour’s flight apart, to an apparent incommunicability?

So, it is because of this curiosity that I have sacrificed my dear and customary shores in the Eastern Mediterranean? I review all the prejudices and fears that dampen the feverish enthusiasm of departure: criminality, dubious HACCP preservation of food, dictatorial governance fresh from a coup d’état, incipient financial default, the height of the migratory crisis, Arab-Neapolitan driving style, raids by marauders from the Tunisian hinterland. I am telling myself stories about how much I will arrogantly think of understanding in 18 days of travel, assuming it is sufficient to dispel the clichés I have just listed one by one. Enough for a restful summer holiday..

The flight is 50 minutes, bathed in sunshine, scorching for window seat fetishists, voyeurs on landing in unknown lands. We fly over our blue sea, stretched out, calm, in all its majesty. At the passport control we are the only Italians, there is only another rowdy Roman family nearby, at the baggage delivery belts I see flights arriving from Tripoli, Misurata, Algiers, something Sahelian. We are in Africa. Let’s take it then, this Tunisian sim, just in case. Outside, a hasty young lady hands us a shiny Suzuki Swift, she is indignant when I ask her if there is 24/7 assistance, just to be sure to be supported in case I lose wheels on the road in the middle of the Tunisian desert, “see you in 18 days at 8.10 at the P5 car park, au revoir”. OK.

Then, hell. It didn’t look like it, crossing the motorway connecting the airport, the Bardo, and various other business districts to the city centre. There was everything I expected, palm-lined boulevards, harmless overtaking left and right, often broken-down cars, billboards advertising fast food or phantom Danone flavoured yoghurts. Suddenly we are at the Clock Tower, at the beginning of Habib Bourguiba Street, and the fury begins. It was supposed to be a long city avenue built in colonial style, with a tree-lined promenade for strolling, the Parisian-style Opera, brasseries, patisseries and cafés. But it is market day – chaos.

Our dar is tucked away in the meanders of the Medina of Tunis, so how do we get there? It takes us about a couple of hours to cover the 4 km or so that separate us from the Cathedral of St Vincent de Paul to the Kasbah Square. We proceed at a walking pace, mopeds and cars shamelessly touch each other, at road crossings the precedence of pedestrians reigns over that of motor vehicles, which easily turn the wrong way, car parks are occupied by clothing stalls, mopeds are very adept at slalom, we communicate with each other strictly by signalling with gestures out of the windows, car arrows are perhaps forbidden? Then street vendors of prickly pears, jasmine, corn on the cob appear, heading towards the square of the Royal Victoria Hotel, the former British Embassy. Why not, at one point even a football ball cuts us off, there are several children playing on the side of the road, between one stall and another. We arrive at the Kasbah multi-storey car park, rather dark, perhaps a little sinister. We are stopped by some (abusive?) parking attendants, I say that I don’t have Tunisian dinars, “je vien de arriver a Tunis, désolé!”, but they wave me through, it doesn’t matter, I can proceed. But how do you pay? Mah, at the exit maybe there’s a guy who will ask us to pay, there, inside a bushel. What happens now though, do the guys from before smash our car? Who knows.

Tunis – The Medina

We are at the gates of the Medina. We have to drag three suitcases along for at least twenty minutes. It is difficult to follow the maps with our hands full, as the gps is confused by the maze of narrow streets, especially when we get lost in the souk. It is time to rely on the first neighbourhood boys sitting at the bar who do their best to help us, then offer us a tour of their soap shops a few steps further on.

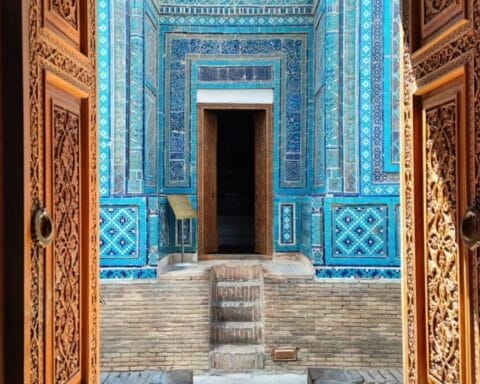

The Dar Zyne la Medina is our stop, the first encounter with the enchanted world of the dar, i.e. old traditional houses converted into accommodation facilities, undisturbed microcosms in which according to an authentic aesthetic experience once can stay and discover Tunisia’s artistic, craft and cultural heritage. They are normally accessed through large gates, with the quality of the door being traditionally a badge of the owner’s wealth: palm wood, more usual and economical, is used for modest houses; apricot, rare and precious, for noble houses. Even their colours hold a special meaning: green is the colour of Paradise, yellow ochre is the colour loved by God, and blue is certainly the most popular. Large nails adorn the surface with symbolic designs, called hilia (‘jewels’), depicting among the main symbols Tanit, the Carthaginian goddess of fertility, the six-pointed Star of David (which according to legend drives away the evil Jinn spirits), the Christian cross, the Muslim mihrab, the Turkish half moon, the eye of Allah, the hand of Fatima and the fish. The doors of the dar separate the hubbub of the Medina from a muffled, private, domestic atmosphere.

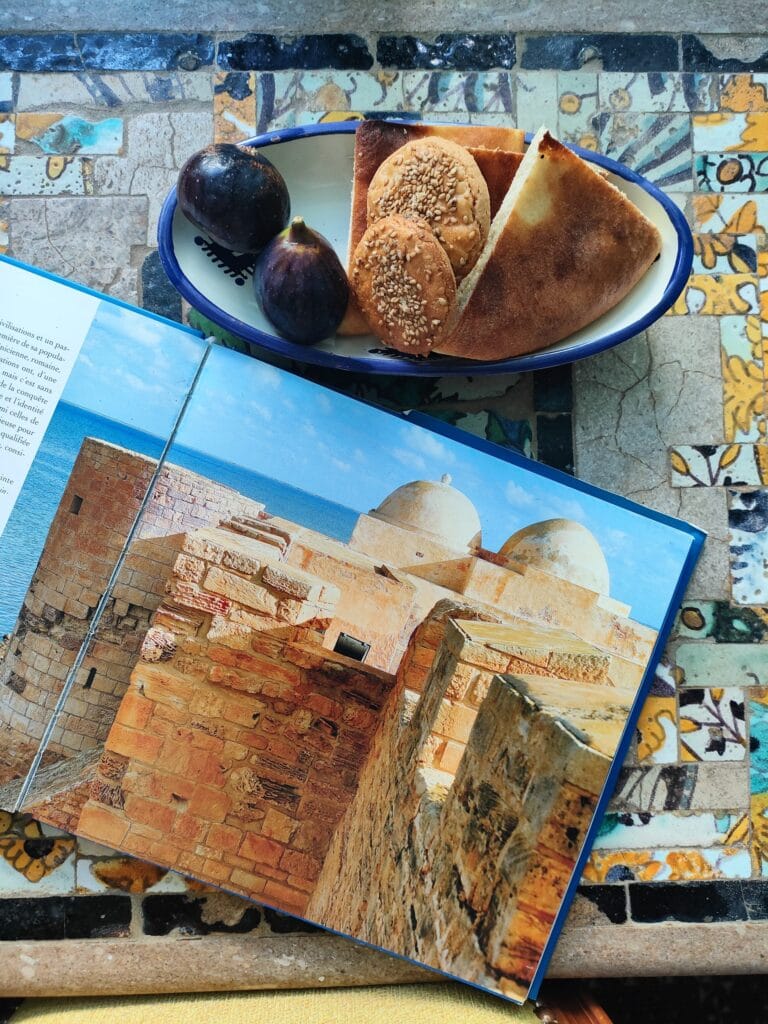

The principle of every dar, be it minute, imposing, sophisticated or meagre, is that all the bedrooms, the kitchen, the storerooms, overlook a large inner courtyard, which is the most fascinating place, the one I prefer. It is where, thanks to a large skylight, one can enjoy natural light, where one can take a nap amidst orange blossoms and placid little fountains, and where breakfast is served, always very rich: fresh figs, watermelon, melon, grapes, eggs, salad, halva, sugary juices, rivers of coffee, mint tea, and mlawi bread, a kind of very tasty crescia accompanied by very sweet jams. There we meet a girl who offers to take us to lunch, perhaps we are looking a little lost. We choose the Fondouk El Attarine, a caravanserai rehabilitated into a luxurious restaurant, craft centre, tea room. My travelling companion is assertive ‘I want to stay here, here is good for me’. At our table, kabkabou, aka the first of a long series of fish stews in tomato sauce, and fish couscous, spicy. The fish is placed, in its entirety, right on top of the well-known pile of shelled pellets. Sophisticated mise en place.

(continues..)