Pity for the nation full of belief but empty of religion

Pity the nation that wears clothes it has not woven, eats bread it has not reaped and drinks wine that has not poured from its presses

Pity for the nation that hails the violent as heroes and considers the ruthless conqueror as generous

Pity for the nation that does not raise its voice except at funerals, that only seeks glories amidst the ruins and does not rebel after it has bent its neck between the stump and the sword

Pity the nation whose ruler is a fox, whose philosopher a conjurer and whose art is the art of patchwork and parody

Pity for the nation that welcomes the new ruler to the sound of a trumpet and bids him farewell with cries of farewell, only to welcome another again to the sound of a trumpet

Pity for the nation in which the wise are rendered dumb by the years and in which the strong men are still in the cradle

Pity for the nation divided into fragments, and each of them believes to be a single nation.

(‘The Garden of the Prophet’, K.G.)

This is how Khalil Gibran described his beloved land, fled and regretted on American soil. The founding reason I had undertaken my trip to Lebanon was precisely this, to see where this inspiring, meaningful, visionary poet and artist was born, briefly lived and died.

The night before, we had arranged to meet the Armenians. Perhaps the next evening we would meet in the late afternoon in Anfeh, the lair of the Lebanese Greek Orthodox cult on the coast not far from Tripoli. A kind of tiny Greek island transplanted on the Lebanese shores. Everything would depend on our plans, which roughly included Bsharre, the Cedar Valley, the Monastery of Saint Anthony of the Maronite order lost in the forests of the Qadisha Valley, the city of Tripoli and finally, perhaps, Anfeh. Through it all, my fellow travel accidentally realised that she was due to catch his return flight to Athens that very night.

That morning, I had breakfast in the hostel with a roommate, she was on duty at the Belgian Embassy. In front of our labneh she told me that there had been terrorist alerts in the area of Tripoli, the Sunni stronghold of Lebanon.

However, I did not know, of course, how we would reach our destinations. A bus operated daily on the Beirut-Bsharre route for about three and a half hours, with no possible connection to the Cedar Valley and Tripoli. I went to the reception desk. Somewhat by accident I met a taxi driver who was waiting to take the service for a group, so I took the opportunity to offer him a daily rate of $70 all inclusive. He offered me $90, and I bluffed that for $90 I would drive everywhere with Uber. “We remain friends, no problem”, I told him. In the meantime, I had thought about repairing elsewhere. Later on, again the taxi driver, a vague Bob Marley look-alike, returned with his smoking cigarette and dishevelled curls. Well.. we had won. They had cancelled his daily shift, so for $70 we left with Ziad.

Ziad was originally from Harissa, a very sunny guy who was cheered by the smoking delicacies of the Bekaa valley.. He spoke English as well as French, just like the majority of Maronite Christian. He was pleased at himself a lot, Ziad, so much so that he alternated between looking at the road and at his silly little curls while looking in the rear-view mirror. He thought, or hoped, that we obviously liked him too, or at least that began to leak out when he suggested we stop for his breakfast-knafeh and showed us that he was the testimonial “OK, thanks for the information”, I think. He also invited me to accompany him to a casting session for a new commercial the following day, he thought we would be a good match. He was very happy to be in the company of two Italian girls. He also tried to prove it to us when, passing through Jounieh, the Monte Carlo of Lebanon, he passed himself off as a great former frequenter of the major night clubs, of which he explained to us the prices (of access, of young ladies from the East or North and Central Africa, of ‘all-inclusive’ packages), characteristics of the main patrons. A questionable attempt to impress. Having ascertained by now that he was irritating and would surely waste our time, I tried to focus on our course.

Bcharre

By noon we had finally arrived in Bcharre.

Lamartine had called the cedars, mentioned in Mesopotamia already in the Epic of Gilgamesh more than 5000 years ago, the ‘most famous natural monuments in the world’. They stretched as far as Syria and Palestine, they had been used to build the temple of Jerusalem, remaining today only in Bcharre, on the peaks of Baruk and in the mountains of the Shuf, clinging to life between the heights, the ice and the wind. The cedar is the symbol of Lebanon, forced into the red and white tricolour of the flag, stamped on passports, painted on the tails of the Middle East Airline, grabbed from the banners of several parties. The cedar is surely the epitome of this country’s great paradox: it appears depicted everywhere, but in fact lies ironically only in the Qadisha valley, in a very precious nature reserve with an almost sacred value (so much so that cedar wood objects can only be manufactured today if the raw material has fallen or died spontaneously). I found and still find it strange that an entire people can universally identify their soul with something that almost no longer exists. In fact, the cedar is the very last real treasure that has survived the martyrdom of wars, it is the untouchable wealth of the country, I guess it represent its immortality.

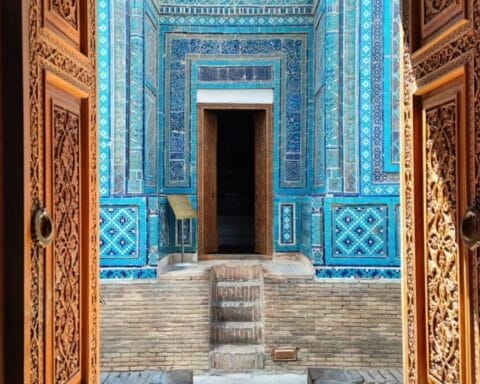

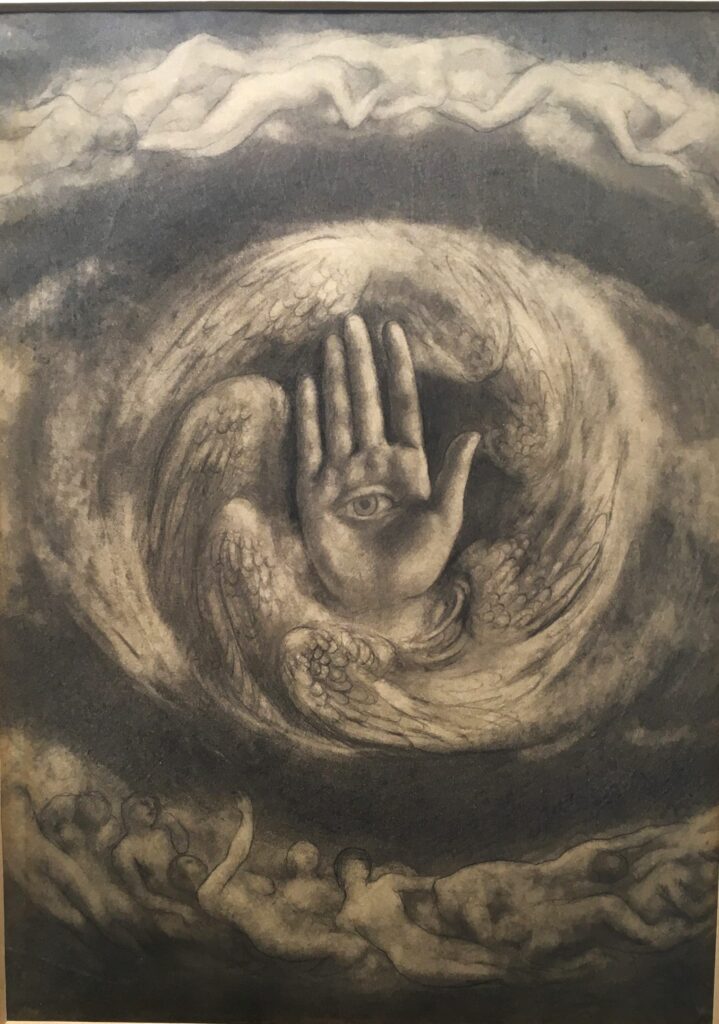

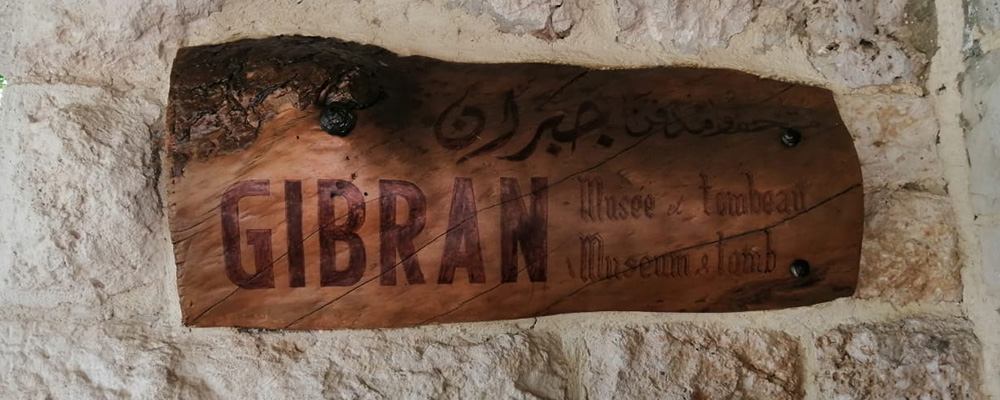

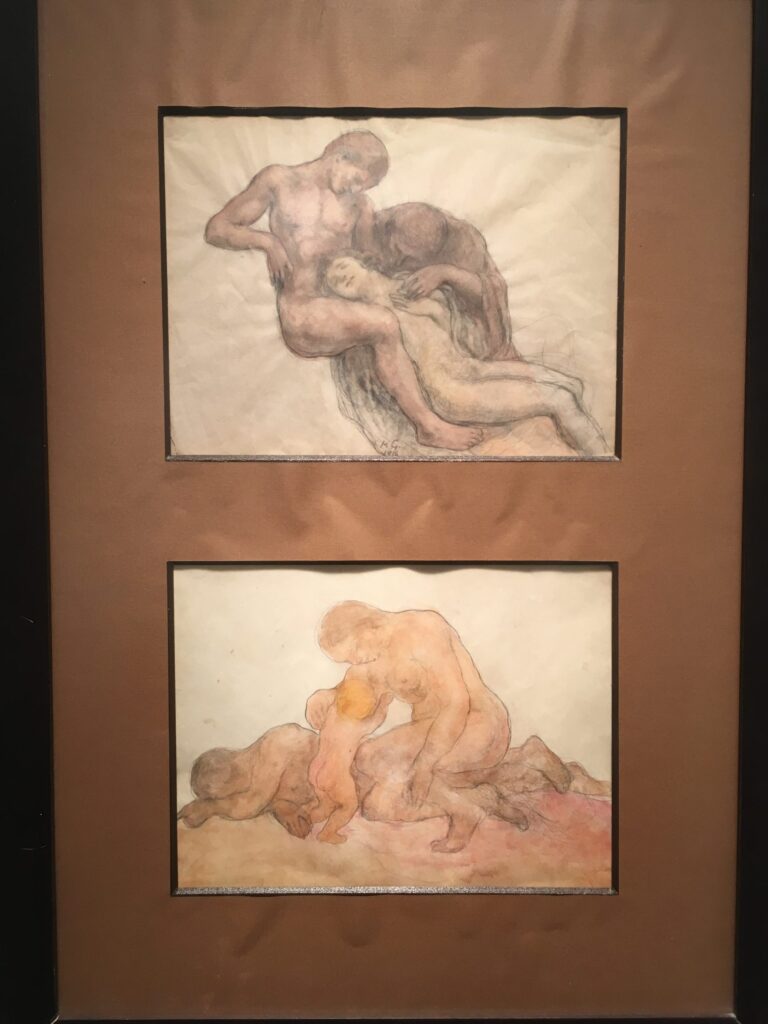

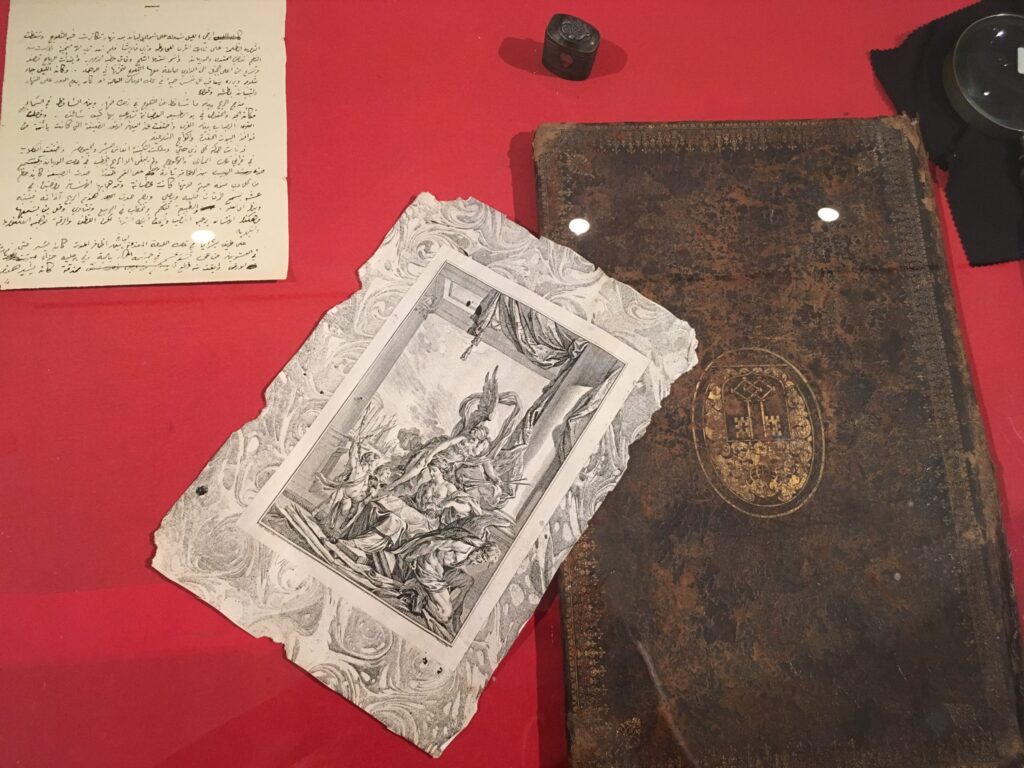

In these parts, on a clear day cooled by the mountain breeze, we came across the tomb-museum of Khalil Gibran. Right in the middle of these woods he himself asked his sisters to bury him, after a life of exile. The museum contained a collection of his writings and major iconographic works, of which I want to mention one in particular, ‘The Divine World’. Mari had told me that her roommate had posted this image right on the threshold of the entrance to his house in Yerevan, and that before going out each time he used to slap a five on the that big eye in the middle of its palm with a slap of five. It looked like a Salvador Dali subject. I would have been later explained that this work, ‘the third eye’, represent the invisible third eye that man has once he has attained his spiritual awareness, beginning to see things from a different perspective or being able to see what was previously ineffable… Personal evolution is simply the increase in sensitivity, to the point where nothing more stands between the individual and reality, and one comes to conceive it in its totality. This is possible because the individual is immanent to matter and God, and therefore has all the resources to comprehend even the highest moment of spirituality. Life is entirely in front of us and needs no intermediary to be understood: an entirely anti-clerical viewpoint. This is why Gibran states that God is here, right now. The thought of this great intellectual is a seductive mixture of mysticism and pragmatism, evolutionism and vitalism, Christianity and pantheism, West and East. The soft gentleness of his verses and the harmoniousness of their rhythm transport the reader to a kind of accessible paradise, where everything is persuasive, scintillating, reassuring, just like his own idea of the transmigration of the soul, and the very fact that God evolves and prescinds from us, without dictating any rules to us. Is he not himself a child of our own construction?

I thought and rethought about this from a wide balcony overlooking the Bcharre valley, while Mari and I waited for Ziad, who had finally decided to visit the museum for the first time in his life, as a citizen. From what I had gathered during that week’s journey, there was only one place to go to understand the Maronites, and that was Bcharre. At the bottom of the Qannubin ravine, the first Maronite hermits found refuge from the Byzantine persecution of the 6th century, fleeing Syria. The town was also known to be the training ground for the troops of the Lebanese Phalange, the party founded by Pierre Gemayel, as well as the home of the famous Samir Geagea, who had led the Phalangist militiamen in the mass murders of Sabra and Chatila, Karantina, Tell el-Za’atar, El-Helvech, besides the execution of his Maronite rivals in their beds. Who knows, many of the men who committed these atrocities could actually be found now perched with a shisha, mint tea or coffee in one of the bars in Bcharre, once a popular ski resort. This village is a cluster of red-roofed stone houses perched on the cliff of Qadisha, occasionally alternating with the towers of a few faux-French Gothic churches, which abounded in number exactly to mark the religious orientation of the place. It probably looked like a European mountain village, if it wasn’t for the extraordinary geological conformation of the place and the aroma of Middle Eastern flavours that placed it geographically further east.

In short, the Qadisha valley, a world heritage site, was a great Christian sanctuary in the mountainous heart of Lebanon, an uninterrupted series of rock monasteries where the echo of ancient prayers in Aramaic, Greek, Latin and Arabic still resounds today. The Christian presence can also be seen in the political posters in the city, all of which belong to Christian parties: yes, here religion is identity, culture, politics, and this is also sanctioned by the Lebanese 1943 multi-confessional and sectarian constitution. The composition of the Lebanese parliament is in fact very strict and divided as follows:

Maronite Catholics: 34 seats

Greek Orthodox Christians: 14 seats

Greek Melkite Catholics: 8 seats

Armenian Apostolics: 5 seats

Armenian Catholics: 1 seat

Evangelical Protestants: 1 seat

Other Christian minorities: 1 seat

Sunnis: 27 seats

Shiites: 27 seats

Alawites: 2 seats

Druze: 8 seats

In addition

– the president of the Republic must always be a Maronite Catholic

– the prime minister must always be a Sunni Muslim

– the president of parliament must always be a Shia Muslim

– the deputy speaker of parliament and the deputy prime minister must always be a Greek Orthodox Christians

And what about the other minorities? For example, could have my Armenian-Lebanese friend ever become Prime Minister, I naively asked myself? The answer is no, and I would soon verify how precisely the minorities represented in parliament but excluded from the top posts have always turned out to be kingmakers in the creation of coalitions or political stalemates, even if they hold a small number of seats. These are flaws in an outdated constitution that smells very much of Mediterranean governance, prone to the maintenance of power groups susceptible to corruption. Better the stasis of rebus sic stantibus, at the cost of not actually having a government leading the country, than the updating of a political system in a more inclusive and efficient sense. Old story.

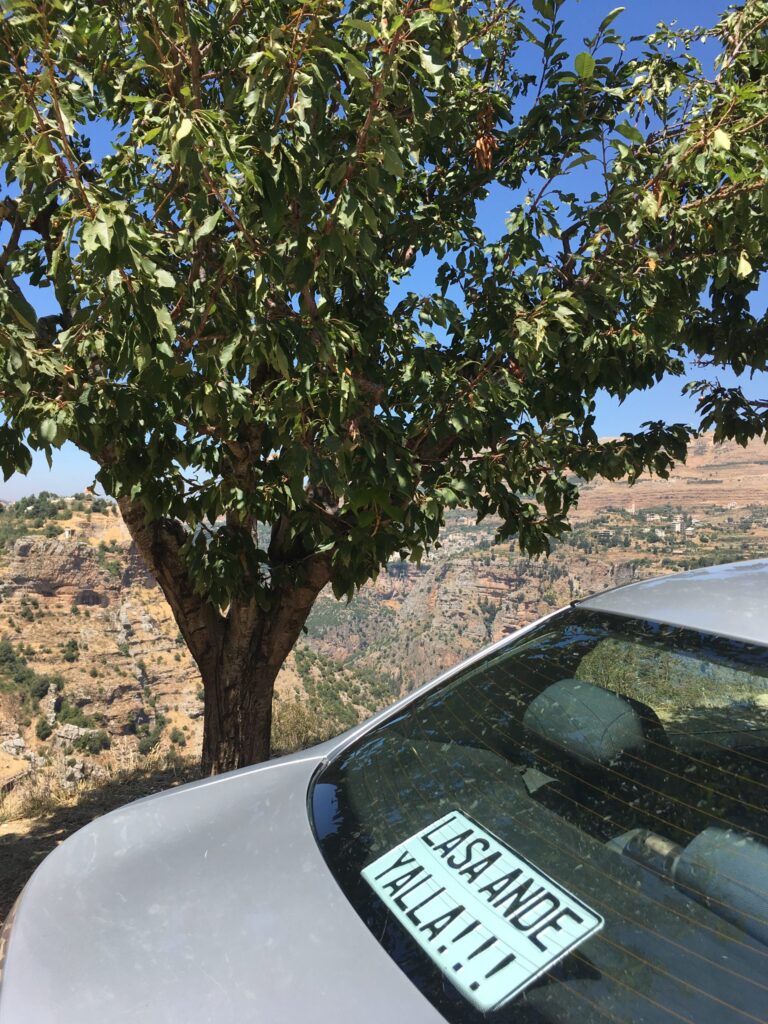

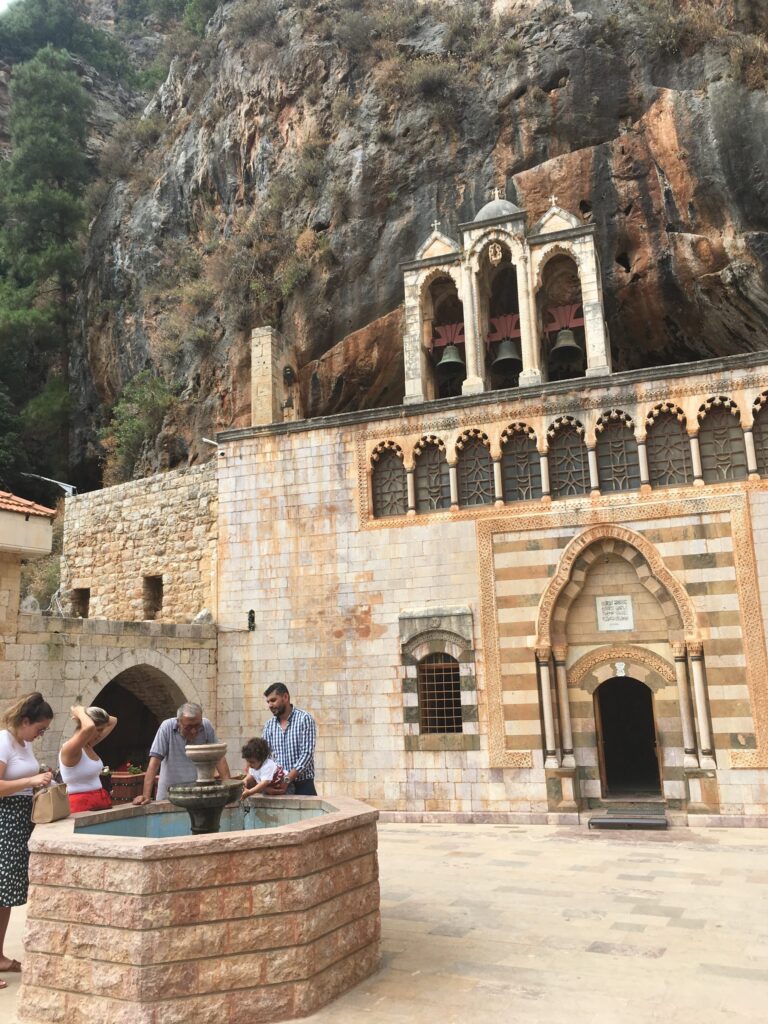

Caught up in the light-heartedness and joviality of the ongoing daily trip, with our google maps jammed and Ziad’s battery dead, I committed a naivety: ‘So..you vote for these buddies I see in the billboards?’ A question asked in the most inappropriate stupidity and qualunquism, which would probably never have caused any upset in Italy. Ziad’s expression changed, his face suddenly darkened, he looked away from the road and looked me in the eye and said: ‘Why are you asking me that?’ At that moment I realised how wrong it had been to ask such a question, albeit naively. How in reality such a question could imply memories, crimes and strong backgrounds in that part of the world. At that very moment I realised that I should never again ask such a question so lightly in that part of the world, or perhaps that I should not even think of asking it at all, without some kind of protection or safeguard. My indiscreet curiosity could wait. His gaze had frozen me. I came to realise that even at the moment of greatest relaxation and fun, the wrong question at the most unexpected moment could change things, making our presence suspicious, our talk pretentious, our sympathy superfluous, his sociability a memory. I changed the subject, reminding him that we had more important things to think about, like getting to St. Anthony’s Monastery in Qozhaya, which he didn’t pretend to forget! But we were all hungry, and Mari had found a wonderful hut without knowing how, it was all written in Arabic even on google (I tentatively remember it was called Cedar’s Heaven or so).

Well, we stopped on a veritable terrace overlooking the valley, sneaking into a Maronite christening party, munching on the usual fattoush, hummus and bath of Lebanese delicacies, including arak.

Would we have ever reached Anfeh?