It is the penultimate day of the year 2024, I am on the snowy road to the city of Gyumri, the ancient Aleksandropol of the tsars, now Armenia.

We are in the hands of Berj, a lovely Armenian driver of Iraqi origin who fled to Yerevan in 2003, when the Americans were bombing Baghdad and dealing with the fate of Saddam Hussein, of whom he is more or less a fan. Berj’s roots lie in Zeytun, Anatolian Turkey, from where his great-great-grandparents left, heading for Mesopotamia to escape Ottoman persecution. Of Mesopotamian ethnicities, religions and cultures, Berj knows a lot, although he seems unaware of it. He is one of those clean souls, free and recalcitrant to the logic of politics who find it hard to attribute “The Bad” to the actions of common human beings, preferring to blame the interests deriving from the superior entity of the raison d etat. When we were at the Areni wine shop he tried, amused, to explain to me how to suck wine from the characteristic clay casks: ‘Like with a demijohn Claudia! We were sucking petrol in the same way from the petrol pumps in Iraq, under the bombs. We often had to go and refuel at night so as not to be spotted’. At the monastery of Khor Virap, opposite the Turkish valley and Mount Ararat, Berj told me about the Yazidis, in front of a ghushbase, a pigeon farm. According to the Old Testament, after the Great Flood a dove brought Noah an olive branch, turning God’s wrath into peace. Buying a pigeon in Armenia and releasing it in a church is today a symbol of good omen towards the new born and the realisation of one’s dreams. Berj exclaims, ‘These are nothing compared to the Yazidi peacocks!’ Yes, the siramarg (peacock in Armenian) is an iconographic symbol found in late antique Christian churches, in the places of worship of Zoroastrianism in Central Asia and Ancient Persia, and finally, in the temples of the peacock angel worshippers, the Yazidis. I only knew that Armenia was home to their largest temple in the world, the Quba Mere Diwane.

Berj I would like to go and see this temple.’

‘Yalla, all right! But we will go to a better place, to one of their villages of about 2000 inhabitants, when we are on our way to Gyumri’.

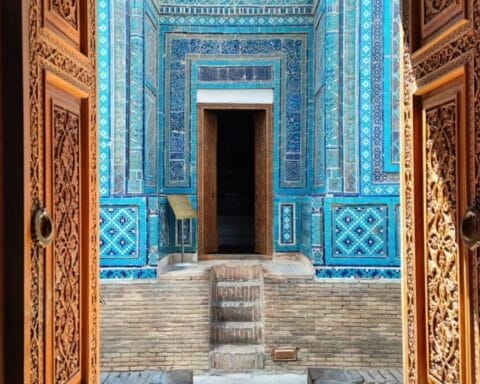

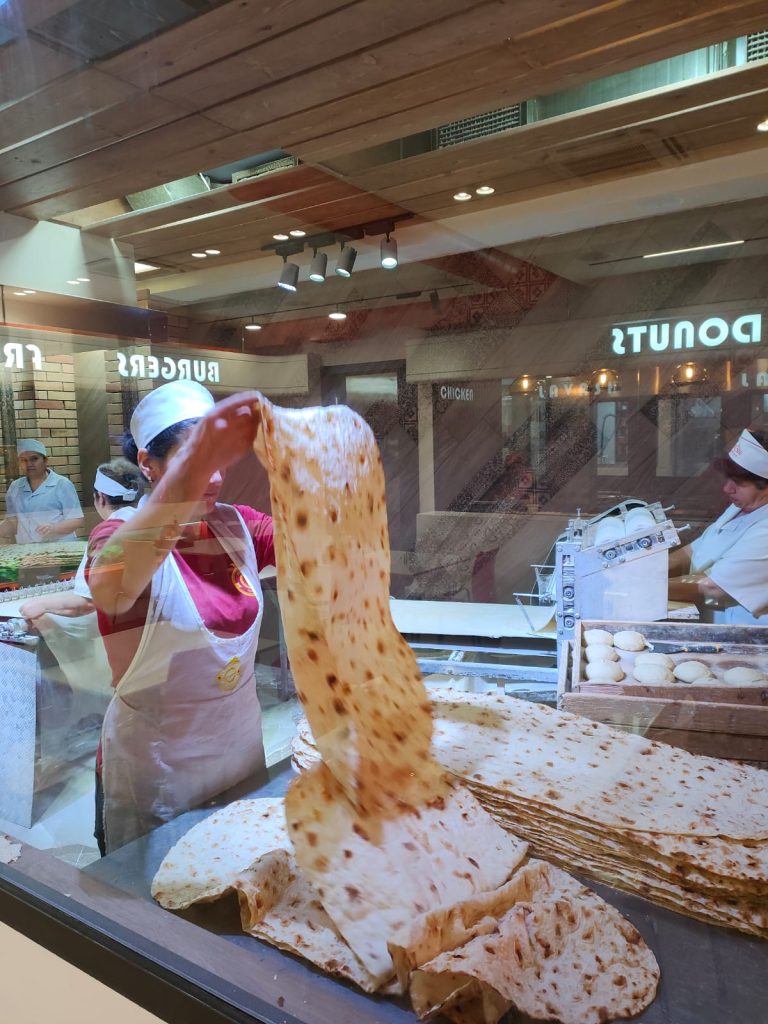

So today we find ourselves on this completely whitewashed roadway, risking getting stuck in the snow when Berj keeps us to a stop not far from Artashavan. He takes us here to see the memorial of the Armenian Alphabet, founded to translate the Bible into the language by the cleric Mesrop Mashtots in 405 AD, who is buried nearby. An understandable stop, considering that these gentlemen are keen to emphasise the role of having been the world’s first Christian state. Just as understandable is the pit-stop at the Aparan food court to taste zhingyalov hats, a kind of lavash stuffed with about twenty herbs, originally from the disputed Artsakh region also known as Nagorno Karabakh.

Then we arrive at Rya Taza. We go down. We see an old sheikh coming out of the temple, although I soon discover that he is 35 years old. I approach him with circumspection and a broad smile. He asks me to take off my shoes to enter, making sure I don’t step on the threshold, which reminds me the same ritual of entering Buddhist temples. He explains to me that the threshold is where the angels dwell. Berj goes to smoke his cigarette and leaves us our privacy.

The sheik and I start communicating in Russian, he explains to me about the village of Rya Taza, how the first Yazidis had come here from the Ottoman persecutions of the 19th century. Of the Yazidis I know just a little, cause of the execrable massacre they suffered between Nineveh and Sinjar (Iraq) at the hands of Isis as the war in Syria broke out. I want to try and know their story as much as possible. The sheikh tells me that they built this temple in 2020, precisely because of the growth of the community following the events in Mesopotamia. He proudly tells me that their religion is Sumerian, pre-Christian, pre-Muslim, and has nothing to do with Zoroastrianism. He is keen to emphasise the uniqueness of this cult even though I can distinguish the contamination with other cults: the veneration of nature (fire, sky, sun, the peacock animal), the call to prayer five times a day, fasting, the ban on eating pork, the transmigration of souls. Finally, I am surprised: this thousand-year-old cult is based on oral tradition, the Yazidis have no sacred scripture of their own, and only recently have they begun to publish texts to try to keep the diasporan community united, which by dogma cannot engage in proselytism.

‘Claudia, when you say..I am a Yazidi, you mean a system of impenetrable millenary organisation, based on intergenerational tradition, on a tribal societal system in which the role of castes plays the very important role of maintaining our identity, our faith, our survival’.

‘What are these castes?

’I am a sheikh, you can only be one by heredity, even women can be sheikhs. I belong to the highest caste and I have the title to take care of the leadership of the community. Then there are the pir, the mentors who are descended from the saint Peer Alae, they can perform religious and secular administration functions; lastly, there are the murid, to whom most Yazidi communes belong.’

‘And what am I?’ I ask like this, just to understand how the “outsiders” are qualified.

‘You are my friend now! We have many American, Indian and European friends who gather here from all over the world in July to support the Yazidi cause. Now I would like to invite you for coffee, two days ago our Sheikh father passed away and a lavish feast was organised in our community. Come with me! You are our guests.’

What was supposed to be a coffee becomes a lunch. The sheikh introduces us to another bearded gentleman, the new chief sheikh, and a peculiar fellow with a head of curly hair. He is having lunch with them, but I see that he looks European.

‘Are you also a Yazidi?’ I ask.

‘No, I am from Lyon, I left on my bike a few months ago and I am passing through Armenia, my arrival point will be Chile. Only when I reach there I will return to France.’

A weirdo. He tells me he is a resigned nuclear engineer escaping capitalist logic. His watchword: happy degrowth. He in turn makes me a coffee in his portable moka. Shortly after, a very shy lady appears, wearing furry slippers, an opaque tunic and a visible moustache. She softens me because she is almost afraid to show up and offer a rich lunch. She seems afraid to interact with us and does not sit at our table. She seems to be willing to, to be imposed to.., remain aloof.

In this moment of conviviality, the salient features of the Yazidi cause and identity emerge. It is as if they want to make us foreigners empathise with their situation, wanting to give voice to the insults they have suffered, fearing that their people will be forgotten in oblivion. Near our table is a poster of Lalish, the spiritual stronghold of the Yazidis, near Mossul. They describe it as a lost paradise, they know they will never return. ‘For us, for the worshippers of the peacock, i.e. the devil, according to the Muslims, there is no room in that land’. This irremediable feud is one of the reasons why the colour blue is a taboo in the Yazidi world: ‘Blue is the colour the Ottoman army and the Muslim Kurds wore when they ravaged our villages. Islam for us represents the enslavement of faith, of the human being,’ the sheikh explains.

We try to play it down by looking at the social network profiles of these gentlemen, they are very active! They show reels with loud Turkish rap and fervent community activities.

Someone exclaims ‘but that’s Turkish music!’

‘No, it’s not Turkish, it’s not, at all’. Sheikh replies resolutely.

The big boss now asks us to sit down. He wants to read us something, he invites the French weirdo to recite a document in English. It is a draft of the Yazidi Statute, which states that only a small number of states recognise the Yazidi Representation. The objective? To claim that the genocide suffered in 2014 will be recognised by the whole international community. There is no precise talk of a compensation. The fulcrum of their lobby is based between Austria and Germany, and it was there that the long sheet we are reading was drawn up, enumerating the victims, the massacres, the international silence, the humiliation. What did I know until then?

I had read a comic book by Zerocalcare, No sleep till Shengal, it briefly mentioned of them. I knew that the crime of genocide against the Yazidis had already been recognised by the United Nations, the European Parliament and several countries including Great Britain and Armenia. The extermination, which began on 3 August 2014, was witnessed by the discovery of more than sixty mass graves in areas of Iraq that were under the control of the Islamic State until 2019. According to estimates released by the United Nations, about 5,000 Yazidi boys and men were abducted and massacred and 7,000 girls and women were sexually enslaved. One of them was Nadia Murad, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2018. Over 3 thousand people are still missing in the Sinjar mountains and Iraqi Kurdistan. I would like to ask what they think of that law, the Yezidi Female Survivors, passed by the Iraqi Parliament in 2021, on the eve of the Pope’s historic visit. This law envisages compensating and reintegrating Christian, Turkmen and Shabak minority members into society: it applies to “any woman who has been abducted, sexually enslaved, sold, separated from her parents, forced to change religion, forced marriage, forced pregnancy and abortion, physically or mentally harmed by Daesh”. It also extends to children ‘under the age of 18 at the time of abduction’ and men ‘who survived mass killings’. However, I dare not ask them their opinion about it. Perhaps this law is not enough, perhaps they are touching it because of it. All I know is that the law is the first legal recognition of ‘genocide’ by the Iraqi government and is a starting point for charging Daesh/Isis with crimes against humanity. I hope they will get the justice they deserve. I think they hope so too, even though they only seem to fear, visibly, that their suffering will be forgotten. They just want their voices to be heard.

It is time to leave, there is still a long icy journey ahead of us to Gyumri. Berj bursts into the hall and says ‘what’s going on with these Yazidis!’, before joining the banquet. Then he exclaims ‘I know Lalish!’, pointing at the poster.

They wish us a safe journey, thanking us for listening to them, leaving us a copy of their local gazette. The sheik stares at me with those black, liquid, absolute eyes: “come back to us soon, dear friends, this is your home, now you know the Yazidis”. Before we leave they ask to take a souvenir photo. Just a moment, I need to go to the kitchen to the cute lady who mastered this generous lunch.

‘Hey, I wanted to tell you that you are an excellent cook, that Georgian salad was delicious! Would you like to take a picture with us?’

’Net..net…” she scoffs.

‘Davaj! Nothing happens, I won’t take the picture if you don’t join, next to me! Take my hand.’

She smiles at me. She holds my hand tightly, I reciprocate.

‘It’s OK,’ I tell her. It seems to me that she is not used to daring so much, that she does not believe she can join us. She smiles at me with embarrassment and genuine happiness – maybe it’s gratitude? I don’t think I deserve it. We all take the picture together, she never lets my hand go.

‘Thank you for having us, my friend, see you soon’, I tell her.

Just like that, we walk off to our journey.